Paul's Mental Workshop, Special page: India

Paul's Mental Workshop- pg 1 | pg 2 | pg 3 | pg 4 | pg 5 | pg 6 | pg 7 | pg 8 | pg 9 |

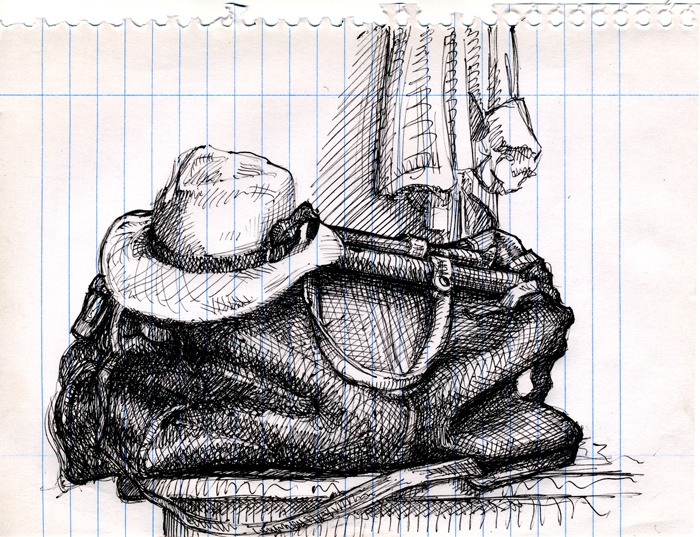

I haven't updated these pages in a couple of months because I was travelling in India. It was a difficult decision but I decided not to take a laptop with me. I wanted to cut the ties with my western reality during the time I travelled but, since I couldn't stop writing, I bought a pad & ballpoint pen & jotted notes & impressions manually. Practically the first hand-written words I've scribbled in years: what a mess! Footnotes, crossed-out lines, addendums referenced on further pages & all without even the first attempt at editing or even re-reading. Another example of how the machine I write on now in lovely word.doc has changed our lives though we assimilated it as a mere slight improvement.

Mostly the writing is inspired directly by the place but from time to time they are simply the thoughts I had while there. I marked the odd page with a date, but, much like my life, chronology & time span is irrelevant & so, rather than attempt to edit the pile into a more pleasing agglomeration I think I will just leave it in the raw. A bunch of impressions & musing written on the several thousand kilometre route I followed.

After getting back to Spain I packed-up & moved to California (the Orient, old Europe & the plastic west coast all within a few months, rather dizzying really) from whence I will now try to wade through the 120 pages of scrawling squiggles to try & extract an interesting presentation, good luck to me & to you, who I hope will enjoy reading it.

Instead of making the low-res images that illustrate this article clickable, I have put them, along with more photos of India, in a thumbnail gallery where you can click for proper enlargements. Some will show information when you hover, both below & on the thumbnail page.

India (18,450 words)

To he whose foot is covered with a shoe the earth seems all

carpeted in leather.

From the Hitopasheda, 12th century AD

Udaipur market, a small painting I did with the worst quality oils I have ever seen & kerosene for lack of turpentine. On teak-wood board 12 x 12 inches (30 x 30 cm)

Travelling by ship is the only transport enjoyable in itself but after the customarily tedious series of flights & stop-overs I was not too tired to notice the nostalgia that washed over me in the taxi from Chhatrapati airport after a 20+ year absence. As the first day of interaction with Indians wore on I noticed my head & hand gesticulations falling in with local usage, from the Spanish to those of the sub-continent: the Gandhi head wag, neither yes or no but a simple assurance all is well without changes; the palm to the sky on crooked elbow, thumb splayed for: what to do? The slight movement of the head on its neck toward the left shoulder while shutting the eyes momentarily, for: sorry, I can't, or won't, or don't want what is offered.

Like

all great cities Bombay, or as it was renamed in 1995: Mumbai, is a

river, constantly moving yet always the same. Its streets are thick

with the intense smells from the foul stenches of life, death &

putrefaction, to the delicate sweetnesses of perfume, spice &

incense. The very smells of humans & of humanity so perfectly

sanitized, deodorized, & cosmetisized in the west, that we are

offended if a person's aromatic presence is anything but

neutralized or perfumed. But where in Thailand the slightest whiff of

body or sewage

brings ready handkerchiefs to delicate nostrils accompanied by

disgusted expressions, here there is an unspoken conspiracy to

valiantly ignore all assaults & people in spotless white

khurtas

will step gingerly over rivulets of raw waste that pour into open

drains as if stepping over spring water in a flowery field. For the

character of India is naught if not accepting & tolerant. It

shrugs

off personal wants to make room for life's vast array of needs

&

variety of abilities.

Like

all great cities Bombay, or as it was renamed in 1995: Mumbai, is a

river, constantly moving yet always the same. Its streets are thick

with the intense smells from the foul stenches of life, death &

putrefaction, to the delicate sweetnesses of perfume, spice &

incense. The very smells of humans & of humanity so perfectly

sanitized, deodorized, & cosmetisized in the west, that we are

offended if a person's aromatic presence is anything but

neutralized or perfumed. But where in Thailand the slightest whiff of

body or sewage

brings ready handkerchiefs to delicate nostrils accompanied by

disgusted expressions, here there is an unspoken conspiracy to

valiantly ignore all assaults & people in spotless white

khurtas

will step gingerly over rivulets of raw waste that pour into open

drains as if stepping over spring water in a flowery field. For the

character of India is naught if not accepting & tolerant. It

shrugs

off personal wants to make room for life's vast array of needs

&

variety of abilities.

The fusion is as unmistakably 'Bombay' as is the mix of brilliant, lacklustre & all the contrasting colours on the grey backdrop of the unpainted & decrepit. The garishness is almost garrulous against the dirt—the way white panes make the dense hues show more saturated in a leaded glass window. And yet, among the crumbling high-rises, the great tapestry of cheap costume jewellery become real gems in shoddy settings.

Among the falling concrete boxes of the 1960's & 70's are others ruined by lack of

maintenance

or worse, by reform. There peeks a twelfth century stone pillar, a

time-softened flagstone floor or an elegant arch leading to an alley

between two atrocities. There are also grand buildings thrown

up during the Raj by Victorian architects gone mad with unlimited

labour. And sprawling corrugated tin & cardboard & plastic-sheet tenements sticking

limpet-like

to ancient temples & new five-star hotels alike.

boxes of the 1960's & 70's are others ruined by lack of

maintenance

or worse, by reform. There peeks a twelfth century stone pillar, a

time-softened flagstone floor or an elegant arch leading to an alley

between two atrocities. There are also grand buildings thrown

up during the Raj by Victorian architects gone mad with unlimited

labour. And sprawling corrugated tin & cardboard & plastic-sheet tenements sticking

limpet-like

to ancient temples & new five-star hotels alike.

The rich, the poor, the hopeless & the

safe cohabit.

Skinny dogs

& homeless people lie where they find space enough &

while they

sleep in the midst of the whirling turmoil they can feel moderately

sure the 'homeful', with beds & kitchens & roofs, will step over, rather than on, their tails or feet.

The rich, the poor, the hopeless & the

safe cohabit.

Skinny dogs

& homeless people lie where they find space enough &

while they

sleep in the midst of the whirling turmoil they can feel moderately

sure the 'homeful', with beds & kitchens & roofs, will step over, rather than on, their tails or feet.

Rampant poverty is in evidence everywhere. The many village people without marketable skills who immigrate into Bombay's false promise, are everywhere living on its streets & washing in its puddles. And yet though they live in misery they are not miserable. Amid Bombay's ill-lit streets mothers watch their children play, too poor even for the small, square, paper kites richer kids duel with from adjacent rooftops, they play instead with a plastic bag on a string, joyful among the cars on filthy pavements.

Stray thought:

When we were children we all wanted to be adult. We saw the privileges of free choice without grasping the sense of responsibility that accompanies it & so we often pretended to be older than our years.

The pretending

might draw amusement, derision or praise as our

elders saw through the farce but from each we learned, until one day,

our acting won us what we sought: a person fooled into thinking we were

indeed adults instead of children.

The pretending

might draw amusement, derision or praise as our

elders saw through the farce but from each we learned, until one day,

our acting won us what we sought: a person fooled into thinking we were

indeed adults instead of children.

After a time this reaction became so common we came to expect it & eventually: to believe it ourselves. But in fact, in our hearts, we are never more than little boys & girls lost to our own illusion.

Goa

The two charming ferries with wooden cabins & white-gloved stewards that brought me to Goa on my first trips are gone. I came by train.

I stopped here in Christian India, the small province 600k south of Bombay first settled by the Portuguese early in the 16th C, to stay with an old friend, Lisa, (the daughter of an even older friend).

Lisa is about my age & has spent most of her life in

Goa where

she now has 21 rooms & a restaurant famous for its good food,

home-grown lettuce (a luxury in India) & home-made buffalo

mozzarella. She is of Italian-American descent & has

restauranting

&  hospitality

in her blood. She runs her staff of 20+ hard though I can see they both

respect & love her.

hospitality

in her blood. She runs her staff of 20+ hard though I can see they both

respect & love her.

She has seen Goa evolve from lawless hippie idyll to Club Med mundanity where the best beach bar, the centre of social interest, plays trance music though there is no Ecstasy to make it enjoyable & has less 'ambiente' than any hole-in-the-wall you can find in any fishing village in Spain where one, at least, needn't haggle the price of a beer down to its actual value.

Today I woke to the shouts of the Nepali staff. I wasn't ready to get up but did never-the-less & dove directly into the shower. As usual I had trouble getting the water to come out the shower head instead of the faucet below but luckily the tap is high up & I am not very tall, so I showered under it instead. Once wet, lathered & shampooed I again crouched under the faucet to rinse but just as I did the flow of water abruptly stopped. I rinsed as best I could with half a bottle of drinking water. I swallowed my toothpaste before coming out to the handsome patio to order coffee with which to rinse my mouth.

When

I complained I had once again, for the third day in a row, had trouble

with the shower Lisa explained they had found a dead animal in the

water deposit (the shouts) & had finally turned the water off

to

drain, clean & refill it. I asked incredulously: Dead animal?

Lisa

said: "Yes, it stunk to high heaven, it's a good thing you didn't

shower in it". I guess I had been too sleepy to notice the smell of

rotting corpse in the water I had washed in while it lasted.

When

I complained I had once again, for the third day in a row, had trouble

with the shower Lisa explained they had found a dead animal in the

water deposit (the shouts) & had finally turned the water off

to

drain, clean & refill it. I asked incredulously: Dead animal?

Lisa

said: "Yes, it stunk to high heaven, it's a good thing you didn't

shower in it". I guess I had been too sleepy to notice the smell of

rotting corpse in the water I had washed in while it lasted.

The

first time I came to Goa was 31 years ago, just a 17 year old kid

thrown accidentally into the world. The last time was 23 years ago when

already the inevitable changes had begun to show. The infrastructure

had always been lacking, there had never been a steady flow of

electricity or water or a space entirely safe from snakes, scorpions,

biting ants or spiders as large as mammals. But the first time I lived

in this small enclave of pristine beaches backed by impenetrable jungle

it was not only youth that made the inconveniences palatable but

attitude.

The

first time I came to Goa was 31 years ago, just a 17 year old kid

thrown accidentally into the world. The last time was 23 years ago when

already the inevitable changes had begun to show. The infrastructure

had always been lacking, there had never been a steady flow of

electricity or water or a space entirely safe from snakes, scorpions,

biting ants or spiders as large as mammals. But the first time I lived

in this small enclave of pristine beaches backed by impenetrable jungle

it was not only youth that made the inconveniences palatable but

attitude.

We made a small utopic community, neither created nor designed but united by the happenstance of place, youth, money (in a poor local economy of sparsely populated fishing villages) many of us were hash traffickers living the rest of the year in Amsterdam & reunited here during the relatively cool months post-monsoon for an ongoing party among our kind, one needn't know the other to assume like-mindedness. Who else, after all, would go there?

We

lived under the sun naked & did what we fancied under the

confused

& marvelled gaze of the locals from whom we rented houses

&

were served. It took no more than one person telling another: "Party

tonight at Bagha beach, spread the word" for hundreds &

sometimes,

thousands, to gather 'round fires & candles in jam jars—all

automatically friends even if we had never laid eyes on each other or

even, if we came from warring countries. Making music with Western

guitars & Indian tablas, small, skin-covered drums, &

buying

hash cakes or acid from those who walked the moonlit beach shouting

their wares carried in baskets over their arms.

We

lived under the sun naked & did what we fancied under the

confused

& marvelled gaze of the locals from whom we rented houses

&

were served. It took no more than one person telling another: "Party

tonight at Bagha beach, spread the word" for hundreds &

sometimes,

thousands, to gather 'round fires & candles in jam jars—all

automatically friends even if we had never laid eyes on each other or

even, if we came from warring countries. Making music with Western

guitars & Indian tablas, small, skin-covered drums, &

buying

hash cakes or acid from those who walked the moonlit beach shouting

their wares carried in baskets over their arms.

Indeed, we made such an interesting zoo that by my later visits organised tours of prudish & sexually repressed Indians began arriving just to look at us. Sometimes one or another of them would remove his sandals to bathe, but never swim, waist-high in the Indian ocean, fully clothed in bell-bottom polyester or saree.

Things have changed, Goa's innocence has gone the way of its European visitors. Now there is as much law enforcement, albeit corrupt & bribable, as anywhere in India. The same drug dealers still come but are now grey, balding, cynical & bloated with money. And the atmosphere is the same as any place that relies on tourism.

The Indians, just  like

us, the same ones willing to put up with a shoddy infrastructure that

offered at least, an alternative to the rat-race, a freedom to love,

laugh & get stoned as a way of life, have organised, become

more

demanding & instead of the marvel, amusement or surprise one

used

like

us, the same ones willing to put up with a shoddy infrastructure that

offered at least, an alternative to the rat-race, a freedom to love,

laugh & get stoned as a way of life, have organised, become

more

demanding & instead of the marvel, amusement or surprise one

used  to see

in their eyes only dollar signs remain.

to see

in their eyes only dollar signs remain.

Big investment has built big hotels & rambling guest-houses. There is a Domino's pizza parlour at Anjuna & where people used to arrive on the 'magic bus' out of Amsterdam (which returned stuffed with hash) now lands an aeroplane filled with rude & strong Israeli backpackers looking to live on a few hundred dollars a year, mixed with ordinary working stiffs on their two week holidays.

As a traveller I leaned long ago it is never a good idea to go back not only because of the inevitable disappointment of inevitable change but because the new memories stain the old.

An old friend wrote & when I answered

from India he responded with comments about his own experience here. On

An old friend wrote & when I answered

from India he responded with comments about his own experience here. On

the

one hand he said India made him feel sadness & anger because of

its

multitudes without "hope or prospect"; while on the other he mused: "If

a culture & country could grow as a direct extension &

manifestation of human nature itself, it would result in something very

like India"

the

one hand he said India made him feel sadness & anger because of

its

multitudes without "hope or prospect"; while on the other he mused: "If

a culture & country could grow as a direct extension &

manifestation of human nature itself, it would result in something very

like India"

I have been pondering these thoughts of his & as I sit under the shade of a spreading Acacia surrounded by the sounds of exotic birds & monkeys crashing through its branches I have come to the conclusion that in the first instance we would have to define 'hopes & prospects' within the context of Indian culture, religion & philosophy, to see if they differ significantly from my friend Dick's, Dutch-Calvinist point of view, before deciding if it is indeed what the poor Indian lacks.

To start with it is often the case that feeling sorry for someone is precisely what turns the subject of our pity into a pitiful figure. If I say to an aboriginal living in a jungle or a desert: "Poor thing, you have no electric toaster, air conditioner, antibiotics or chemicals to rid your house of insects" or any of the other things that make me feel I am lucky & he unlucky, I am in effect teaching him he is is disgraced by their lack.

If a poor urban Indian's only hope & prospect is surviving the present moment, achieving it will give him as much satisfaction as say, publishing a book after years of work might be to Dick (who is an (excellent) author). One tourist might not consider his holiday's day full if he hasn't quaffed a bottle of expensive imported champagne at breakfast while another finds satisfaction in getting through the day on a dollar or less. It is always a dangerous pitfall to impose one's own value system on others.

If

there were a pill to induce depression just as there is to alleviate

it, the effect on global culture would be very like television's has

been. As its window blinks open in the world's remotest parts it

provides both mesmerizing delight & tantalizing frustration to

those who look through it to see unreachable worlds. The delight is in

the easy fantasy television's

content provides while the frustration occurs at the vision of a

glamorized ordinary life.

If

there were a pill to induce depression just as there is to alleviate

it, the effect on global culture would be very like television's has

been. As its window blinks open in the world's remotest parts it

provides both mesmerizing delight & tantalizing frustration to

those who look through it to see unreachable worlds. The delight is in

the easy fantasy television's

content provides while the frustration occurs at the vision of a

glamorized ordinary life.

From the shopkeeper in Marrakech's souk to the Bedouin in the Gobi desert, handsome actors in two thousand dollar suits are aided by expert cosmeticians & lighting teams to convince him that any ordinary, often American, life, is far better than his own & that unbeknownst to himself he has been all along no more than a pitiful figure without hope or prospect.

India especially should be exempt from the burden of our pity, common respect is received with far greater felicity. Merely remembering someone's difficult-to-the-western-ear name can have more weight with the name's owner than a coin in his palm.

When one makes acquaintances with Bombay's street people, as I have, one finds he partakes of the same emotional range, the same unattained desires, delights & disappointments as most.

Hinduism embraces acceptance, it invented the second chance, betterment in the next life as reward for living out Dharma correctly in this.

As to the observation Dick made that India is, in a sense, a macrocosm of human nature, as a symbolic metaphor rather than a literal one it gives food for thought because just as we as individuals are none of us of one type or another, but rather all of us are all of the possibilities but in different measure, India's great circus of paradox has a unified character.

Despite its slight, if harsh policing, India is hugely under-governed. Its practical laws are pragmatically enforced by a lack of privacy. The thief, the wife-beater, the social parasite in whatever form is seen. A community so dense in members controls itself because the extreme proximity of its individuals (it is not unusual for an Indian's territory to be reduced to the actual volume of his body) means there is a witness for nearly all deeds.

On a crowded train those who don't fit or simply haven't the money for a seat or litter will sleep on the floor & those who have paid won't feel put out by the fact they must lift their feet or avoid getting up at night so as not to step on anyone. The Indian often lives within such a small kinesphere he might not feel his space invaded until you actually sit on his lap.

But instead of all agreeing to an unwritten law that, living so closely, each should try to be circumspect with the next, for instance: trying to be quiet while others sleep, as a Confucian oriental might, or as driver, instead of waiting his turn he will all merge whenever he can even if it means he whose turn it is must wait (likely resulting in the same drive-time as being polite), the same goes for smells or light that bother others. They choose tolerance over consideration, forbearance over cooperation.

Bollywood

It is a significant irony in itself that the fellow who stopped me in the Colaba market (Bombay) did so standing in front of the McDonald's, albeit a McDonald's where if you ask: Where's the beef? You'll find their really is none; because he was looking for westerners to act as extras in a Bollywood film, I, of course, agreed at once.

The following day at five in the afternoon a motley crowd of non Indians gathered in front of the same McDonald's & about an hour later were on a bus for the two hour ride from Bombay to the Bollywood studios. Among the thirty or so recruits of all adult ages were Africans from Nigeria & Ethiopia, various European countries, the Americas, China & Japan, & even some Aussies & Kiwis.

On both days, that of the recruitment & that of the filming, we were warned repeatedly not to bring things of value & not to let our possessions out of sight.

Upon arrival we were taken directly to wardrobe, men & women were separated & we were outfitted with either suits meant to look like 1920's England, or waiter outfits, black trousers & waistcoats, bow ties & white shirts, & strangely: black cowboy hats. We changed together right there on the spot under the full moon & were then told to dump all of our valuable possessions in a pile in an unguarded room far from the set.

The

set was impressive with a two story pseudo-grecian façade

maybe

100 metres long replete with life size sculptures in niches & a

large balcony from which the heroine looks down on her lover as he

walks through the tables scattered across the perfect lawn peopled by

us foreigners. It was meant to be London in 1922 but the women were

dressed as inappropriately as the men in a cross between Scarlet O'hara

& gay 90's impressionist opulence.

The

set was impressive with a two story pseudo-grecian façade

maybe

100 metres long replete with life size sculptures in niches & a

large balcony from which the heroine looks down on her lover as he

walks through the tables scattered across the perfect lawn peopled by

us foreigners. It was meant to be London in 1922 but the women were

dressed as inappropriately as the men in a cross between Scarlet O'hara

& gay 90's impressionist opulence.

Apparently the film, 'Veer', was already in post-production & we were there only to shoot a few missing or failed scenes. It was a Salman Khan film, an actor with godly status here in India. He commands more than a million dollars per picture (a bona-fide fortune in this economy) & is releasing three this same month. Known as Bollywood's bad boy he is still, at 45, Indian audiences' favourite romantic lead as well as a media darling with his image not only all over the press but also on billboards, advertising, television & posters wherever you look.

I

have worked on many sets usually in the art department (in what seems

another life-time) but have never seen or even imagined a film of any sort

could be shot so sloppily, much less one likely to see box office

receipts of over 50 million dollars. Bollywood fans are as faithful as

they are undiscriminating.

I

have worked on many sets usually in the art department (in what seems

another life-time) but have never seen or even imagined a film of any sort

could be shot so sloppily, much less one likely to see box office

receipts of over 50 million dollars. Bollywood fans are as faithful as

they are undiscriminating.

The director was a disembodied voice in the sky, booming through huge speakers spread in the trees, which sometimes called: "action! cut! back to your places!" & sometimes either shouted other things instead or nothing at all; the fact not all of us understood his improvisations & either stood our ground through the action or failed to return to our places for the next take didn't seem to bother anyone at all. I, the humble extra dressed as waiter, seemed the only one of the hundreds on set that cared a fig for such details as continuity.

And then: a hush fell on the multitude & the great man himself walked on set. Khan followed by two gym-giants dressed in black & three others who fussed with his hair, his face & his immaculate clothes. I pulled out my camera but one of the men in black rushed over to inform me that photographing Mr Kahn was not allowed (I got one shot anyway, below in white suit silhouetted against the lights).

He limited the display of his acting talents to a muscly swaggering before the camera & a lowering of his chin to look fulminatingly, if expressionlessly, into the lens.

I had directions for a route through the tables, talk to the guests at the first, serve drinks from my tray at the second & stop at the third where I was captivated by a winking green-eyed Irish woman whose lightning wit thrilled. We talked through several takes & she told me she was on sabbatical from her job as Sony's marketing director in Ireland.

When we commented on Khan's apparent lack of acting skills I said: "well, he has an impressive body for a man his age, it must take a lot of hours at the gym" she answered: "Furthermore he seems preternaturally clean, indeed, he appears to be a positively sterile object among the all-too-human" I countered: "Yes, I'm sure he doesn't pick his nose." without missing a beat she answered: "no, I'm sure he has someone who does that for him".

After a few takes the director descended from the sky

& incorporated right before me, a fifty year  old

man with long receding hair, to speak to me about an idea so brilliant

he could barely describe it through his giggles: as the great star

walked past me to his love on the terrace above, he is so engrossed in

her beauty (& not without reason—pictured left) he bumps into me without even

noticing.

old

man with long receding hair, to speak to me about an idea so brilliant

he could barely describe it through his giggles: as the great star

walked past me to his love on the terrace above, he is so engrossed in

her beauty (& not without reason—pictured left) he bumps into me without even

noticing.

He told me expressly to turn away from the table to my right in order to set up the accidental collision. Although this made little sense since it put Khan within my line of vision before the jostle, I took the direction without comment.

The first take went like a charm, Louise, the Irish girl, encouraged me in my big starring break with winks & even the suggestion we improv: "when he bumps into you" she said "turn with a good right cross to his jaw, when he falls I'll kick him in the groin. Don't worry Paul I've got your back"

And on she went in the same vein blinking her big pale eyes & making her boyfriend nervous enough to come running over between shots. And so, under the banks of lights, the camera boom on rails fixed on us & within the steady gaze of the hushed crew, Louise made easy bon mots & I cracked up, delighted as always by a woman with a sense of humour, as if we were all alone.

I told Louise that since I couldn't see Salman's approach she should give me the nod when he was close. It was then, however, the director came back with an even more brilliant idea, smiling & smirking at his own ingenuity he said: "instead of a nudge why don't you go ahead & fall to the ground?" & he directed the three women at Louise's table to laugh when I did.

When

he added as afterthought: "say, I'm sorry sir" as if flustered by the

faux pas of being knocked to the ground by one of the guests, I

became the only extra with a spoken line & what's more, in

tight

frame with India's most celebrated actor.

When

he added as afterthought: "say, I'm sorry sir" as if flustered by the

faux pas of being knocked to the ground by one of the guests, I

became the only extra with a spoken line & what's more, in

tight

frame with India's most celebrated actor.

Again, despite the awkward choreography, it came off without a hitch, I kept my head down so that I might credibly appear not to notice his approach & allowed myself to be knocked over. On that first take, which I was sure was a keeper, Salman offered me his hand to get back to my feet, for the rest he left me where I lie.

The director came running up again actually laughing at the sophisticated wit of the scene but told me: "No, no, you must fall more" &, rubbing his hands, added: "do you know Charlie Chaplin?" At which Louise & I burst into another fit of uncontrolled laughter.

But we did at least another dozen takes without ever again coinciding. Louise would give me the nod but he repeatedly sabotaged the timing by doing things like stopping a single pace away from me & we would end up looking at each other, I bemused, he: on the verge of a starry tantrum at having to work with such incompetents but afraid to move his face, endlessly fussed over by the make-up people, for fear it might crack.

A couple of more attempts & the director came back, this time I got him to hear my suggestion I turn to the left instead of the right & he looked at me as if I were daft: "yes, of course, turn to your left"...

But

still we didn't coincide. One of the director's many minions came up

once & asking my name said: "when it is time to turn I'll shout

'Paul'" to which I readily agreed. I was beginning to feel a little

nervous as the unwavering stare of the crew & actors clearly

blamed

me instead of their country's greatest artist. But not only did I never

hear my name shouted (on that take I stood my ground, waiting, as Salman

walked past) but I never saw the minion again.

But

still we didn't coincide. One of the director's many minions came up

once & asking my name said: "when it is time to turn I'll shout

'Paul'" to which I readily agreed. I was beginning to feel a little

nervous as the unwavering stare of the crew & actors clearly

blamed

me instead of their country's greatest artist. But not only did I never

hear my name shouted (on that take I stood my ground, waiting, as Salman

walked past) but I never saw the minion again.

On another try Khan actually spoke, & what's more, to me, fixing his big black eyes on mine he said, not without lordly benevolence: "can you hear me when I make this noise?" & he made a rough sound in his throat which he could do without moving his face. I assented & he said: "I will make that noise when it is time for you to turn toward me." I stood & waited, when he made the noise I turned only to find him still three metres away...

Without any explanation offered, or which I can imagine, there were shouts & the entire set went into motion, the extensive lighting, its diffusers & reflectors, the rails & camera that ran on them, the all-important smoke machines & lackeys all rotated like a creaky giant & half an hour later we filmed my getting up from the ground after my fall, Salman a pace past me, at an entirely different angle from the table the women sat at & with completely different lighting.

The shoot went on until sun-up & I met a few interesting people including a very engaging old man, an architecture buff who, like me, is a great Frank Lloyd Wright fan & from Buffalo where I worked at Wright's Darwin D. Martin house when at university; & a pretty Chinese girl that writes for a lady's magazine who agreed to go out with me the following day.

In short: I had a ball as well as an interesting experience. I was paid 500 Rupees for the night's work, about 10 bucks, but though they asked me back I declined thinking once was an experience, twice was just badly paid work.

I look forward to seeing it, Veer, when it comes out.

The welcome

As I walked up to a relatively expensive restaurant in Bombay a mother, father & their seven or eight year old boy opened the door before I reached it & walked out. The boy separated from his parents & veered off toward me. His family were momentarily disconcerted even making a micro-movement as if to pull him back but he had already reached me. Looking up into my eyes with a beaming smile he offered me his hand & said: welcome to India.

His Mum & Dad broke into laughter & I returned his handshake, his smile & thanked him with the same sincerity as the welcome he offered.

Chor bazaar, Bombay

I remember the Chor bazaar as a sprawling flea market filled with junk, antiques & interesting things like mountain healers who cured lesions with poultices made of live iguana blood; odd items left behind by the pre-independence Raj like old books & Victrola record players.

Today I found it

deteriorated into the most pathetic market I

have

ever seen, untouchables selling items I can't imagine anyone picking up

off the ground for free much less paying for. In this lowest of

commerce conducted by the abjectly poor I again thought of Dick's pity

for just this sort of Indian's hopeless lack of prospects. None of the

sellers expected me, a foreigner (i.e. rich) to buy the wares he spread

on old potato sacks on the ground amid rivulets of raw sewage, but

delighted instead at the rareness of my presence as representative of

my privileged class. I ate exquisite delicacies prepared at the

most rudimentary of stalls & wrapped in newspaper.

Today I found it

deteriorated into the most pathetic market I

have

ever seen, untouchables selling items I can't imagine anyone picking up

off the ground for free much less paying for. In this lowest of

commerce conducted by the abjectly poor I again thought of Dick's pity

for just this sort of Indian's hopeless lack of prospects. None of the

sellers expected me, a foreigner (i.e. rich) to buy the wares he spread

on old potato sacks on the ground amid rivulets of raw sewage, but

delighted instead at the rareness of my presence as representative of

my privileged class. I ate exquisite delicacies prepared at the

most rudimentary of stalls & wrapped in newspaper.

I found that as symbol of riches & power beyond not

only their

prospects but even their wildest imagination, they did not see, for

instance, my camera as the equivalent of a year's labour—something to

angrily resent as desirable yet out of their reach—but rather as an

object of fun which they innocently asked to share in, posing with

broad smiles at the experience, though they would never see the photos.

Where I might wish

for & even suffer for the impossibility of

attaining Bill Gates' wealth, Brad Pitt's beauty or Mick Jagger's fame,

their absence of superfluous ambition actually puts happiness within

easier reach for them than I.

Where I might wish

for & even suffer for the impossibility of

attaining Bill Gates' wealth, Brad Pitt's beauty or Mick Jagger's fame,

their absence of superfluous ambition actually puts happiness within

easier reach for them than I.

Jaipur

Jaipur is a beautiful city. The first planned city in all of India, the Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II and the Bengali Guru Vidyadhar followed the instructions of the Vastu Shastra written 10,000 years ago by Mamuni Mayan (translates roughly to 'the science of architecture' often consulted in the construction of temples but never before in a city) for both intelligent practical usage & mystical congruence. The eastern gate of the fortifying wall is called 'Suraj pol' or sun gate & the western: Chand pol (moon gate), its streets & boulevards are measured in multiples of nine for the planets.

It

is known as the pink city because what is not built of rose sandstone

is washed with red clay & walls throughout are decorated in a

cream

pattern, below.

It

is known as the pink city because what is not built of rose sandstone

is washed with red clay & walls throughout are decorated in a

cream

pattern, below.

It

has a long tradition of marble sculpting, usually Hindu gods. It is

India's third largest city & is a city of contrasts but in a

different way to Bombay. Here the sprawling & spreading urban

ugliness of cheap concrete boxes in which the modern India shelters,

contradicts an opulent, even extravagant history of building by

fabulously wealthy Rajput Maharajas, while Bombay's greatest splendours

were left behind by the British Empire in a fusion of styles known as

Indo-Saracen.

It

has a long tradition of marble sculpting, usually Hindu gods. It is

India's third largest city & is a city of contrasts but in a

different way to Bombay. Here the sprawling & spreading urban

ugliness of cheap concrete boxes in which the modern India shelters,

contradicts an opulent, even extravagant history of building by

fabulously wealthy Rajput Maharajas, while Bombay's greatest splendours

were left behind by the British Empire in a fusion of styles known as

Indo-Saracen.

Yesterday I walked with a friend under a steady drizzle refusing the persistent rickshaws that drew close to offer their services. Despite the discomfort of the unusual weather we enjoyed the time walking gives to see the details, make eye contact, have a broken-English conversation or try some hitherto unknown delicacy from one small & dingy shop or another.

Before entering the walls of the old city we ran across another meatless McDonald's (an expensive night out for the average Indian family) complete with a plastic, life-sized statue of Ronald himself sat on a bench, arm extended along the back, inane smile under clown's make-up.

This

sparkling-clean Ronald McDonald, however, was covered in dirty,

dirt-poor urchins & it struck me as the very image of clueless

American Imperialist expansionism. I managed to snap a few photos

before the street children noticed & ruined the photo-op with

self-consciousness.

This

sparkling-clean Ronald McDonald, however, was covered in dirty,

dirt-poor urchins & it struck me as the very image of clueless

American Imperialist expansionism. I managed to snap a few photos

before the street children noticed & ruined the photo-op with

self-consciousness.

When they did they jumped up as one to beg for money. Once surrounded I put my camera in its bag & reached into my pocket for money but pulled out a larger wad than I had intended & the circle closed uncomfortably around me.

I looked at the girls ranging from around five to eighteen years old & peeled a relatively large bill from the rest & they were already grasping. I made a gesture that it was to be shared before handing it to the eldest.

As soon as I did they attacked like the Spanish gypsies used to do in Sevilla before tourism's value became understood & the Guardia Civil taught them not to with heavy billy clubs. They pressed against me, their small hands all over me even reaching into my pockets. With the camera in one hand & the money in the other the best I could manage at first was simply holding them both too high for the girls to reach.

I

made brusque & threatening gesture that made them retreat

slightly

& momentarily while filling the vacuum on the opposite side. In

a

moment, more joined their ranks & I was afraid I would have to

resort to violence to extricate myself before being overwhelmed. I was,

never-the-less, aware what a rare opportunity this made for a dramatic

series of photographs & so shouted to my friend who stood like

a

deer caught in headlights, "Are you getting this?"

I

made brusque & threatening gesture that made them retreat

slightly

& momentarily while filling the vacuum on the opposite side. In

a

moment, more joined their ranks & I was afraid I would have to

resort to violence to extricate myself before being overwhelmed. I was,

never-the-less, aware what a rare opportunity this made for a dramatic

series of photographs & so shouted to my friend who stood like

a

deer caught in headlights, "Are you getting this?"

Finally I chose the biggest for a sharp open-palmed shove to the chest which sent her flying to land heavily on her behind. She made no sound & though it must have hurt she got up again without hesitation to immediately rejoin the fray. They insisted; cringing with closed eyes at my movements without attempting to evade them. They were obviously willing to take a blow in exchange of a coin, a meal, a chance at another day's survival.

With an abrupt & graceless movement I finally broke through the circle & with my friend (whose camera had, unfortunately, seized-up during the melee) moved briskly into the crowded street where it would be difficult for them to surround me. And yet one little girl, about seven & dressed in rags, with an ugly scar that crossed from brow to cheek with a pure white eyeball in its middle, followed us for about a kilometre. I would have liked to give her a few coins but had learned my lesson: this was too desperate a neighbourhood to risk generosity. I can only hope the eldest bought samosas all 'round with the bill I gave her.

Indian saying: A Man is unfinished until he marries... & then he is finished.

The antiques dealer, Saturday 14th of November

I

stopped in an antiques shop yesterday to look at Mughal miniatures to

add to my small collection though one can no longer buy the

antique ones as I used to do in my long ago visits. I spent an hour or

so looking at what the shop owner had, using his thick glasses as

magnifying lens to judge their quality.

I

stopped in an antiques shop yesterday to look at Mughal miniatures to

add to my small collection though one can no longer buy the

antique ones as I used to do in my long ago visits. I spent an hour or

so looking at what the shop owner had, using his thick glasses as

magnifying lens to judge their quality.

He had some wonderful pieces from the south in the Orissa style, wildly exuberant & lively but the prices were high & I don't know them well enough to confidently negotiate the right one.

When I finished looking, without buying anything, the counter was covered in small paintings & under them: a packet of cigarettes with my brass Zippo, my old friend, inside. I had noticed how fascinating Indians found the lighter which they don't have here & it had been difficult to find fuel for it. Out of sight I forgot about it & walked out leaving it behind after thanking him for his time. By the time I realised, I was already across town & by the time I got back he was closed.

After breakfast this morning I tried again. The owner greeted

me

with the kind of anticipatory hopefulness a returning client inspires.  His

assistants ran around turning all the lights on (they are kept off to

save on electricity between clients). I had still said nothing but I

could see it wasn't promising. Still I hoped he might just be trying

his luck & would return the lighter when asked. But when he casually

picked up a silver trinket from the counter-top, the only object not

under glass, & had an assistant remove it, I knew I was in for

a

fight.

His

assistants ran around turning all the lights on (they are kept off to

save on electricity between clients). I had still said nothing but I

could see it wasn't promising. Still I hoped he might just be trying

his luck & would return the lighter when asked. But when he casually

picked up a silver trinket from the counter-top, the only object not

under glass, & had an assistant remove it, I knew I was in for

a

fight.

When he finally faced me across the glass counter under which I could see the piles of paintings I had looked at yesterday, I explained I had forgotten a box of Marlboros with a lighter in it & had come back to pick it up. At first he pretended not to understand, when I repeated he spoke briefly to his scared-looking staff in Hindi before turning back to me & assuring me it wasn't there. Had I perhaps left them somewhere else? "No" I insisted, "there is no question: I left them here". He looked cursorily on the floor behind the counter, shrugged his shoulders & repeated: "They are not here." "They were when I left yesterday" to which he countered: "we don't smoke, why would we want to keep your lighter?" "Because it is valuable" I answered.

He then flew into a sudden fit of anger, informing me they were not thieves, my accusations offended him & he even jabbed his finger very near my chest as he looked down on me fiercely from his greater height through his thick glasses (he was Kashmiri). His assistants were quiet & nervous & in all fairness, there was still room for doubt one of them had taken it unbeknownst to the owner.

I stayed calm & said simply: "it was here when I left

yesterday,

if it is not here now it is because someone here took it away. He tried

another gambit: "If another customer came in after you & took

it,

there is nothing I can do about that". I restricted my response to a

not-worth-answering smirk. He again became vehement saying: "Do you

want me to call the police?" to which I answered evenly: "yes, please"

though I wasn't entirely convinced India's entirely corrupt guardians

of justice wouldn't simply take advantage of the conflict to get a

bribe before letting me leave.

But

I needn't have wondered as he answered my affirmative with an

arm-waving, theatrical, menace: "Why should I call the police?"

"Because you just offered". He shouted a bit more & I simply

said:

"I'll be back" hoping I sounded like Shwarzenager.

But

I needn't have wondered as he answered my affirmative with an

arm-waving, theatrical, menace: "Why should I call the police?"

"Because you just offered". He shouted a bit more & I simply

said:

"I'll be back" hoping I sounded like Shwarzenager.

Once outside however, I doubted there was anything further I could do. There was no evidence but my word for an accusation of theft & nothing the police could do even if they were my greatest champions. Anything might have happened to the lighter & unless it was found on the premises, the only part of my story they were sure to believe was that I had lost it. Still, I left convinced he lied, sure he had removed the little silver jug from the counter-top when I entered for fear that in an altercation I might grab it & run out the door with it.

As a visitor, a guest in India, I felt more saddened than angry. It wasn't after all, the first Zippo I'd lost.

When my driver came to pick me up this afternoon I told him the story. He laughed easily & assured me I shouldn't worry, he would get my lighter back. I couldn't imagine how, if the shop owner now admitted having it he also admitted his intention of stealing it & he must know as well as I that I have no legal recourse nor am I, a tourist, likely to take it up in gangster style. When we arrived at the shop my driver, Om, told me to wait in the car.

After about ten minutes he came out to ask me in. The antiquarian & his staff of three stood in a huddle in the middle of the shop & seemed a little disconcerted though Om was calm & smiling.

The owner blustered: "you can search my shop all you want!" To which I replied: "But I find it easy to believe it is not here".

At this he turned to the boy, the youngest of his employees at

about

sixteen & more likely an indentured servant from the north than

a

salaried employee; he was of low caste & poorly dressed

& when

the shopkeeper spoke to him in Urdu, with angry inflection, the boy  looked

bewildered, scared & non-plussed. He then turned back to me

&

said in English: I just found out it was him, I am so sorry, I am

ashamed that such a thing could happen in my shop, we are honest

people. God gave me much money & I don't need to..." &

interrupting himself he turned again with even greater anger toward the

boy with raised arm as if to strike him. Before he could actually slap

him though, I spoke up saying it was alright & asking where the

lighter was now.

looked

bewildered, scared & non-plussed. He then turned back to me

&

said in English: I just found out it was him, I am so sorry, I am

ashamed that such a thing could happen in my shop, we are honest

people. God gave me much money & I don't need to..." &

interrupting himself he turned again with even greater anger toward the

boy with raised arm as if to strike him. Before he could actually slap

him though, I spoke up saying it was alright & asking where the

lighter was now.

He spoke to the boy & though I couldn't understand him, the effort the boy made to understand his boss was clear for all to see. Finally, hesitatingly, he reached under the counter, eye still on his boss as if to check he was doing it right, & he pulled a folder stuffed with papers from under the counter. When he loosed the string that held the papers in a bundle I saw the packet of Marlboros & retrieved it. Inside was the lighter &, mysteriously, only one cigarette which was not a Marlboro.

The tall Kashmiri declared to me: "I want you to take him to the police!" I answered with an Indian head-wag & said it was okay. He offered me his big hand but I ignored it reaching to offer my own to the boy instead before leaving without more ado. I never learned how Om changed his mind about keeping it.

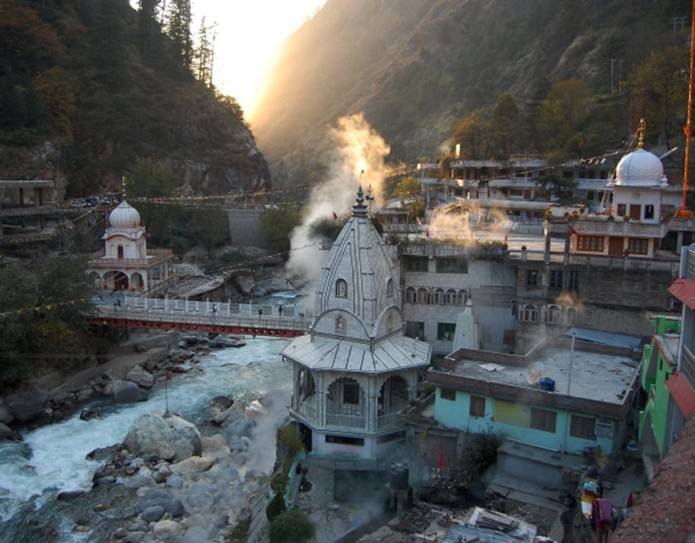

Pushkar

Pushkar is one of India's most sacred places as Lord Brahma was born here. In Sanskrit 'push' means flower & 'kar': hand. They are joined to name this town because when Brahma died & rose to heaven, Shiva reached through the sky to drop a flower on the spot his mortal body fell. And on that place one of India's most important temples has stood nearly 1000 years. It is a vegetarian town where no animal is killed.

Upon arrival I was bullied more than conducted by my guide to the ghats where I was handed ceremonial coconuts & a priest attempted to tie a blessed string around my wrist & paint a prayer bindi on my forehead in exchange of money. Although I am accustomed to showing ritual respect in all the sacred places I visit, this felt all wrong & I refused. Having broken the assembly line of tourists bustled here directly from their vehicles, made the priests aggressively angry.

I had dinner with Miani, a young man born & raised in Pushkar, his passion moved me. His grandfather had been head priest in Pushkar's largest temple, carrying on old wisdom under British rule. Miani had instead grown with the example of idealistic young hippies who followed Lennon, Leary & Baba Ram Das to spiritual illumination in the magical East still only recently indepedent of British rule.

As we ate & then rolled joints of his excellent charras he talked to me about his point of view, the one garnered under the combined influence of ancient cultural & religious roots, & enthusiastic discovery from the stream of starry-eyed foreigners who talked with him, laughed with him, slept with him.

He said he remembered how when he was young the holy men still had power which one could feel in their touch. Now the same temple his grandfather had run, the one I could see over his shoulder & under a setting sun as we spoke, put someone at the door to charge an entrance fee to tourists like me, tourists interested in history,

art & architecture, not the spiritual purpose of the building. They let people carry their shoes (for fear they might be stolen at the door) a lack of respect equivalent to wearing them, & they no longer minded if a woman defiled the temple with her menstrual cycle as long as she paid for her ticket.

Miani

went on to say the fourth age, the age of darkness his grandfather

predicted, had begun. In the first age there were only the gods, the

second began with their creation of the world. The third was when the

wise men, the enlightened, the holy men, roamed the earth to guide

& set example for confused mortals. The fourth is when the

demons

man created survive him, & the final abandonment by the gods.

Miani

went on to say the fourth age, the age of darkness his grandfather

predicted, had begun. In the first age there were only the gods, the

second began with their creation of the world. The third was when the

wise men, the enlightened, the holy men, roamed the earth to guide

& set example for confused mortals. The fourth is when the

demons

man created survive him, & the final abandonment by the gods.

He asked: "Haven't you noticed how our mother earth has again become

our enemy as in days of old when the tiger was mightier than man

&

the rivers stronger than man's ability to control them?"

Pushkar's lake was traditionally believed to be bottomless until the

Mughal Emperor, Jehangir, who like his father embraced all religions

but hated superstition, had it measured & determined it was

nowhere

deeper than twelve cubits. When I arrived it was empty & the

wide

range of water birds that swooped over & under its surface were

displaced. As he talked I could see across the sprawl of ugly concrete

on whose rooftops monkeys cavorted & children played with their

small, square kites, the big muddy hole surrounded by forlorn temples

on whose steps morning ablutions were undertaken as long as history in

the sanctified waters; & now only cows, monkeys, pigs &

mangy

dogs foraged amid its rubbish.

The lake had become a toxic hole disgusting with the waste of its streaming pilgrims & growing population & Miani told me how the government had decided to first kill the fish, presumably to be able to collect them all instead of their lying all over the bed of the waterless lake.

Six million fish, six million, he emphasised & his voice trembled when he told me how the whole town stunk of their death before they were gathered in nets & shovelled onto overflowing trucks to be carted off. A shock to a town that hasn't seen an animal killed, nor even an egg eaten, in a millenium.

Pushkar has gone from dozens of centuries as unspoilt spiritual mecca coloured in its every facet by religious ritual through a rapid evolution as subject for Victorian watercolorists & engravers pandering to isle-bound vicarious adventurers, to object of digital images taken by a steady procession of clueless tourists whose only purpose is to impress friends back home (in the real world) with their exotic experience when in fact they might have gone to Italy instead if only the exchange on the dollar wesn't so damned low.

Jain

Some

of India's most beautiful temples are not Hindu but Jain, one of the

world's oldest religions. Its most recent jinna or 'conqueror

Some

of India's most beautiful temples are not Hindu but Jain, one of the

world's oldest religions. Its most recent jinna or 'conqueror  of the inner self' was Mahavira born 550 BC, the twenty-fourth ascetic

master often portrayed standing with the vines that grew around his

legs as he meditated, oblivious to all, the world, his hunger, his need

of sleep. In one temple I asked the priest why one of its murals

portrayed Mahavira in the lotus position with a man holding a stick

that traversed his head, in one ear & out the other. He

explained

it was a story of the man who was offended when Mahavira didn't return

his salutation, at first he shouted, but to no avail. It was only when

Mahavira continued meditating quietly even after the man had run the

stick straight through his head that he realised Mahavira was truly of the

enlightened.

of the inner self' was Mahavira born 550 BC, the twenty-fourth ascetic

master often portrayed standing with the vines that grew around his

legs as he meditated, oblivious to all, the world, his hunger, his need

of sleep. In one temple I asked the priest why one of its murals

portrayed Mahavira in the lotus position with a man holding a stick

that traversed his head, in one ear & out the other. He

explained

it was a story of the man who was offended when Mahavira didn't return

his salutation, at first he shouted, but to no avail. It was only when

Mahavira continued meditating quietly even after the man had run the

stick straight through his head that he realised Mahavira was truly of the

enlightened.

The Jain do not believe in any God but rather in five cosmic principles

based on doing no harm to any living thing, & the perfect

structure

of the universe which they want to spiritually join, without making any

change which, since the universe is perfect, could only make it less good.

There are fewer than 5 million Jain in the world, mostly in the south of India where the devout walk the world sky-clad (i.e. naked). They carry brooms with which they sweep the path they will trod clear of any small animal they might otherwise accidentally hurt with their footfall. Their religion's precepts have influenced India's culture in a measure far larger than the proportional number of devout.

Right:

plates on which food from market stalls is served. They are pressed of

green leaves that retain their shape once dry.

Right:

plates on which food from market stalls is served. They are pressed of

green leaves that retain their shape once dry.

When finished eating from them they are thrown wherever one happens to be standing & within a short while they degrade into individual leaves again.

Jodhpur

Between here & the Eastern frontier roam India's national symbol, the peacock, looking impossibly decorative against the dry, yellow-grey desert backdrop & at night, they wail like babies in distress.

Although cows are sacred here they are used for labour & milk. Ghee, cow-milk butter made less perishable by being clarified & reduced, is used in place of oil. The cows that roam free may have once been domestic livestock but liberated by a farmer in thanks' of a good crop, a son's wedding or other celebration of good fortune. Or it might be born its own master; domesticated yet wild, living in an urban centre just as wild animals live in the jungle, mountain or desert. Whether it crosses a busy highway or mills among city traffic & pedestrians, it looks neither left or right, showing little interest in anything, moving in slow motion as the world whizzes around it.

I saw one temple that was built 8 hundred years ago with ghee to mix the mortar because the drought meant they had no water.

Today, however, I saw something I didn't know still existed: running in the desert a genuinely wild cow, a cow of the breed that has never been domesticated. They are called Neel Ghai here & are blue-grey, taller than their city cousins, stronger through the front quarters & as fast as big deer.

A

friend & I walked up the hill to Jodhpur's incredible &

apparently impregnable fort (rising like a rock in the image at left)

when a neatly combed little boy of about 9,

dressed in the short pants of a school uniform with his books in a

satchel asked me for the pen with which I write this. But since he

didn't look like he needed it & it was the only one I had, I

didn't

give it to him. He then told me he saves coins from foreign countries,

did I have any from my country to give him? A ploy I had already heard

enough times to know that though a bank won't change coins to local

currency there is a trade in them which must involve the collection

& transport of large quantities back to their home countries. I

carried on walking & didn't notice that he also approached my

friend who lagged a few steps behind. My friend didn't look closely,

assumed he was a beggar instead of the middle-class boy of high caste

that he was, & gave him a hand-out. My friend walked past him but

when I turned I could see the boy holding the coin aloft between thumb

& forefinger, a smile of wonder & pride on his face, to show it

off to the elders of the neighbourhood, who all, in turn, smiled

proudly back at him. I have been saddened to see India's

evolution

from being a country with a high percentage of poor people reduced to

begging, to becoming a country of beggars.

A

friend & I walked up the hill to Jodhpur's incredible &

apparently impregnable fort (rising like a rock in the image at left)

when a neatly combed little boy of about 9,

dressed in the short pants of a school uniform with his books in a

satchel asked me for the pen with which I write this. But since he

didn't look like he needed it & it was the only one I had, I

didn't

give it to him. He then told me he saves coins from foreign countries,

did I have any from my country to give him? A ploy I had already heard

enough times to know that though a bank won't change coins to local

currency there is a trade in them which must involve the collection

& transport of large quantities back to their home countries. I

carried on walking & didn't notice that he also approached my

friend who lagged a few steps behind. My friend didn't look closely,

assumed he was a beggar instead of the middle-class boy of high caste

that he was, & gave him a hand-out. My friend walked past him but

when I turned I could see the boy holding the coin aloft between thumb

& forefinger, a smile of wonder & pride on his face, to show it

off to the elders of the neighbourhood, who all, in turn, smiled

proudly back at him. I have been saddened to see India's

evolution

from being a country with a high percentage of poor people reduced to

begging, to becoming a country of beggars.

In Bombay I had been surprised by the number of young mothers (very young) often with a breast uncovered & a baby, always asleep, who asked for a handout but refused offers of money. They insisted instead, I go with them to a pharmacy to buy baby formula. If I refused to go to the shop with them, why refuse my money? It turns out they are involved in a huge Oliver Twist style organised racket where young women are imported from poor villages in Rajasthan & given babies doped with opium to carry around. They are watched over to make sure they have no earnings they might hide for themselves outside of the monies divided between corrupt pharmacies, the bosses, & lastly, the basic subsistence expenses of keeping the girls in a place they can sleep & eat together as their only recompense.

As I became more & more aware that India's developing tourism includes a subdivision of burgeoning beggary both professional & amateur, I bemoaned the effect new income is having on old, proud, Indian culture.

By

the time I got to Jaiselmer after following an admittedly foolish

touristic route through colourful Rajasthan, I found myself faced with

a uniformed guard, the same one who had checked my ticket for paid

entry into a Jain temple, asking me for money for "watching my shoes"

while I was inside. I was finally outraged. We were surrounded by

people in the small square before the temple doors & I spoke

loudly: "Shame on you! I have left my shoes at the entrance of a

hundred temples & mosques all over the world but here in your

town

I must pay to insure they are not stolen? This is a holy place

&

you are not a poor man, you are among those lucky enough to have paid

work but you are willing to give up your dignity for a few coins? And

in Rajasthani: harijan nai? (harijan is the word introduced by Gandhiji

to replace the more offensive 'untouchable', it means 'children of

God'.) i.e. the gist of my meaning was: are you an untouchable without

more recourse than begging for your food?

By

the time I got to Jaiselmer after following an admittedly foolish

touristic route through colourful Rajasthan, I found myself faced with

a uniformed guard, the same one who had checked my ticket for paid

entry into a Jain temple, asking me for money for "watching my shoes"

while I was inside. I was finally outraged. We were surrounded by

people in the small square before the temple doors & I spoke

loudly: "Shame on you! I have left my shoes at the entrance of a

hundred temples & mosques all over the world but here in your

town

I must pay to insure they are not stolen? This is a holy place

&

you are not a poor man, you are among those lucky enough to have paid

work but you are willing to give up your dignity for a few coins? And

in Rajasthani: harijan nai? (harijan is the word introduced by Gandhiji

to replace the more offensive 'untouchable', it means 'children of

God'.) i.e. the gist of my meaning was: are you an untouchable without

more recourse than begging for your food?

He shrunk back, palms facing me & said: "up to you, up to you..." but I insisted: "I know it is up to me, I don't need your permission", & once more I repeated: "Shame on you"

I was gratified to notice that the Indians all around, both local & tourists looked on seriously & some even showed assent with nodding heads.

Where I have found the same open-hearted, generous, friendly hospitality & sense of 'humanness' (often lacking for instance in an exquisitely polite interaction in Thailand) that has always been typical of India, everywhere I go now, in the touristic hot-spots it seems we tourists have taught them that, more than humans carrying wallets, we are wallets incidentally accompanied by humans.

Not only are they now willing to charge for entry to a place of worship (just as we do in Europe) but there are guides with memorised patter, though generally incapable of answering any but the most superficial questions, who kickback to priests who follow them around to make sure they don't lie about their earnings & who will themselves also bully shamelessly for 'donations to the temple'.

Worst of all in a country with a deep historical respect for personal spirituality, the search for wisdom or enlightenment, are the saddhus who renounce the material to practice instead a combination of ascetics & meditation in order to overcome samsara (the wheel of suffering pictured on India's flag) & the illusion of reality or, conversely, reality's illusion—to search for higher universal truths. Now they don the orange robes & sit before temples of any denomination selling the rights to photograph them to sightseers (see photo at the top of this page). They watch television instead of meditating & wear prosperous paunches instead of practicing ascetics.

Indeed, some have taken the begging bowl to full commercial exploitation where gifts meant to improve the giver's karma are collected wholesale & the teacher, the saddhu, the seeker of higher planes of consciousness, is driven around in BMWs followed by armed guards as he amasses his earthly fortune.

We tourists, if not the travellers, have corrupted with easy earthly pleasures; what is a small expense, like a good hotel room, to a member of a first-world working class, can be the equivalent of a month's honest work in the third world. And an honest, artless price paid for a closer look at a culture amounts instead in its purchase & removal.

I remember a girlfriend in the south of Spain in the years before the European Union & a single European currency were introduced. She made a comment about not liking the idea & I was surprised. "Why don't you want a union formed? It will bring Spain a lot of money & everybody who lives here will be better off." She answered: "Why would money make us better off? We have always been poor & we have a right to be poor. They will give us money but take our culture." A scant couple of decades later I can see for myself that she was right. The Andalucia closer to its six-centuries old Moorish past then the twentieth century, is, today in the twenty-first, filled instead with people stressed & anxious to live the American dream, even as they fall short.

Spain went from just above Greece (traditionally the poorest) to just below France. A house in the south of Spain now costs as much as one in Tuscany & many cashed in on the windfall, giving up the ancestral home built of stone to be able to buy large television screens for their new concrete condos. And now that they all know what a BMW looks like they are no longer happy with a Renault; in which way are they better off? Rampant tourism has shown Spain which parts of her culture have value by paying for them—thus turning them from culture to performance, & the Spaniard has become an American wanna-be while contradictorily despising American culture.

I remember the open, lazy Andalucia made up of far flung villages some of which could only be reached by donkey, villages nearly self-sufficent & proud of old traditions—I miss it. The Spanish hat & cape has gone the way of India's turban & long moustache. Spending more money each year of life is the sum of the American dream, relishing acquisitive power more than the things in themselves; even a poor uneducated Indian goes deeper than that, let us not pity him, we should respect him instead.

There have been psychological studies that show the lottery winner & the man converted to paraplegic, each reach a range of emotions equivalent to that they had before the accident, happy or otherwise, within a year. Should we go up to the person in a wheelchair, pat him on the head from our greater height & tell him: "poor thing, you can't walk anymore, I feel for you"? So why do we condescend to the Indian so? The man sleeping in the street, resting his head on his own orthopaedic leg—at the top of this page, is known for his jolly personality.

Do Ghai, Indian (Brahma) cows, oils on wood panel 12 x 12 inches (30 x 30 cm)

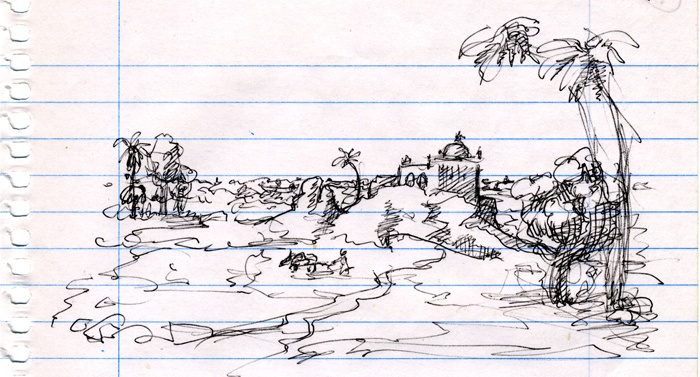

I spent the day & night with Vivendra, an Indian artist I was introduced to. He & his family have been living in his rambling house & spacious studios for 21 years. He sows crops, at this time of year: mustard, on his few hectares. Around them are many more hectares which hold a shallow lake & fields used for harvest, sparely scattered with country houses & the odd building.

Like the Renaissance engravings of Florence that fascinated me so as a child, the trees & palms receded infinitely on a desert as flat as a puddle of water all the way to its horizons.

Vivendra is from Jaipur, one of four large cities in the strip of desert called Rajasthan that ends in the 200 kilometres of sand dunes that reach from behind the 12th century city of Jaiselmer to the borders of Pakistan in the north. He has become involved with the local community. He organised, for instance, the rebuilding of the dung school house into a far less charming but much more functional concrete building where around 140 kids, from 6 to 12, from the farms & surrounding villages get educated.

He encourages the area's rich crafts tradition—at only an hour's drive from Jaipur still too remote to find commercial outlet—while at the same time worrying about the cultural impact commercial success brings. After begging the government these last 11 years he has been allotted fifteen hectares nearby his home (about 40 acres) where he intends to set up workshops for local artisans as well as a marketing & distribution infrastructure.

Vivendra's house seemed to me a locus of creativity & his studios were littered with work by other artists, students & craftspeople, sometimes even in collaboration.

From his immense rooftop terrace my eye was drawn by the only hillock on the flat plain that surrounded us. Its ragged stone peak was surmounted by an interesting looking ruin with an intact cupola. I asked Vivendra: "Temple?" & he answered "500 years old"

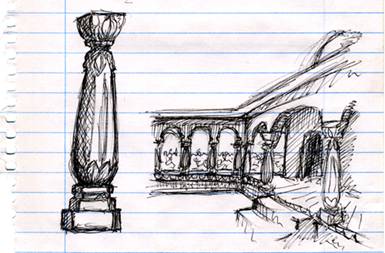

It was a fifteen minute walk through fields of yellow mustard, past a goatherd & skirting the shallow lake before we reached the ruined temple. As it turned out the stones that capped the hill were grey granite as was the temple. It had beautiful if naïf granite columns with lotus motifs on capital & shaft that supported delicate arches through which, it seemed, one could see to infinity.

There were still about 150 square metres of temple standing

covered,

including the dome over the old altar, approximately 4 metres in

diameter. Another 250 square metres of walls whose roofs had caved-in

& probably the same again in foundations with varying levels of

crumbling stone walls.  Some of

the pillars of the fallen arches had already been carted off to be used

in local homes.

Some of

the pillars of the fallen arches had already been carted off to be used

in local homes.

Without roof it will not last many more monsoons.

Looking at it I was moved by the thought that though it has seen twenty generations of men born & die it will probably revert to a pile of the stone it was made of within my life-time, indistinguishable from the rest lying all around. And it occurred to me that with labour prices such as they are here as little as $20,000 could just about get the place restored, or at least: secured & roofed.

I spoke to Vivendra about it & he told me it could not be purchased because it is not owned; it belongs to the community at large but contractual rights to its use could be secured & he felt the grateful community would surely support such a scheme with enthusiasm.

I

suggested an artists colony. A few motivated artists with a couple

thousand bucks each could get the project started. Further funds could

be solicited from people like gallery owners or arts magazines who

could advertise their involvement in a project to save a historical

building destined to be put at the disposal of creative endeavour.

I

suggested an artists colony. A few motivated artists with a couple

thousand bucks each could get the project started. Further funds could

be solicited from people like gallery owners or arts magazines who

could advertise their involvement in a project to save a historical

building destined to be put at the disposal of creative endeavour.

The original altar could be returned to its use as place of worship while the rest could provide at least a dozen spacious & unique studios a few looking out in one direction or another from the height of the hill with a beautiful communal courtyard. A community of interested artists or university students could be rallied & organized using no more than social networking Sites dedicated to the arts.

A standard tourist Visa to India is six months & the place might attract landscape painters or people painters. Or those who want to learn new techniques & mediums from local artisans or even just to enjoy working in the quiet, beautiful & exotic surroundings.