page 2

Wednesday

August 19th, 2009

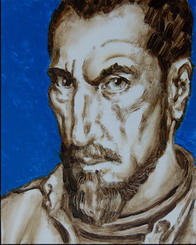

Christ’s devil (2080

words)

In the original Christian universe, the one where the starry skies

whirled around the world, Paradise was above the clouds just out of

man’s reach, and Hell in the unspeakable depths beneath

his feet; there was but one God and his only interest and

affection was fixated on a flat piece of earth filled with innately

important humans surrounded by all the plants and animals placed

at their disposal—to serve as fuel for the divine purpose of human

imperialistic expansionism.

In Islamic tradition Lucifer (Iblis- إبليس) is a fallen angel (jinn)

the same as in the Christian texts but he is exiled from heaven for

disobeying Allah by refusing to bow before Adam though he would before

his creator.

In the Christian tradition Lucifer is one

of more fallen angels whose unforgivable sin (unforgivable because an

angel doesn’t need faith: he has knowledge instead) of

arrogating to a power equal to his creator’s, the

creator: God his father’s, without whom nothing but,

presumably, He, would exist.

-

How art thou fallen from heaven

O day-star, son of the morning!

How art thou cast down to the ground,

That didst cast lots over the nations!

-

“…you have come

to a dreadful end and shall be no more forever”

And unlike the Muslim belief, it happened

in the morally pristine spheres that were the world before the

introduction of the apple of God’s eye: humanity.

Since the Gnostics, the beginnings of Christianity and the

Catholic Church, there have been theologians as wise as philosophers* who have added complex moral

symbolism, interpretation or apologia for, or to, the stories.

Lucifer is symbolised by Venus his name meaning: ‘the light

of the morning’ or ‘the light bearer’,

like Apollo before him, he who was brought low by the capital sin of superbia

or conceit. He began his career after the fall not as God’s

nemesis, his moral inverse or competitor for the souls of men, but

rather as his agent, he who looked for evil and reported it to an

omnipotent and omniscient but apparently, distracted, God.

But Lucifer’s legend grew and evolved, and

artists who found him more interesting or priests who converted from

convincing man to follow the Christian creed through a desire for

God’s love to the more effective gambit of scaring the piss

out of them with the devil’s wrath, aided his fleshing-out

and filling-in until he became the alternate king reigning over

the other side of the axis of power.

Popes, monks, folkloric tradition, painters and poets worked over

centuries to bring Lucifer’s character to life, during the

low Renaissance Dante adds lovely poetic flourishes with the image of a

devil that reigns over the nine circles of Hell, himself stuck in the

lowest, trapped by ice waist high. He flaps his great black wings in an

eternal attempt to rise while the cold wind generated by those same

wings freeze the waters that hold him.

Or Milton a few centuries later who continues moulding

Lucifer’s image in his books really intended to address the

question of why an omnipotent God would allow evil within his creation.

The conflict between His divine and eternal foresight and

man’s free will. A benevolent and omnipotent God could

simply disallow evil in his universe if he cared to, if he does not,

does that not make him evil also? And if he cannot, then is he worthy

of adoration?

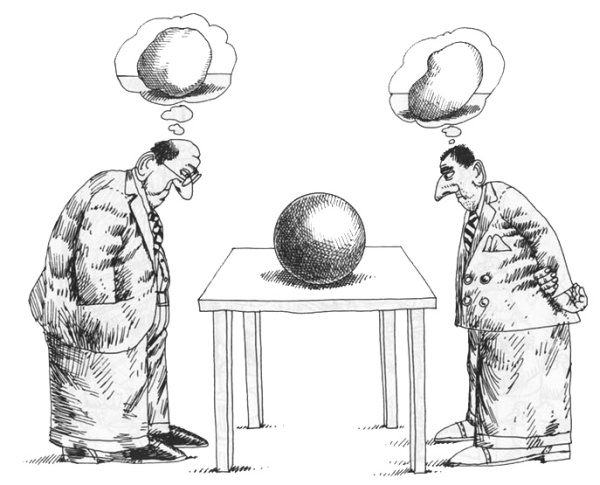

The Christian God therefore becomes an infinitely informed chess player

who stands for moral righteousness and rewards it with eternal

bliss and understanding, while his opponent (with the black

pieces) tempts man’s faith in goodness by offering immediate,

if short-term, delights. From the Qur’an:

-

He said: Then go down hence! It is

not for thee to show pride here, so go forth! Lo! Thou art of those

degraded.

Lucifer said: Now, because Thou hast sent me astray, verily I shall

lurk in ambush for them on Thy Right Path.

Then I shall come upon them from before them and from behind them and

from their right hands and from their left hands, and Thou wilt not

find them beholden unto Thee.

He said: Go forth from hence, degraded, banished. As for such of them

as follow thee, surely I will fill hell with all of you

‘I’, says the creator

in the last line, “-will fill Hell with all of

you”. Satan can convince God to punish man for taking his

(Lucifer’s) counsel but hasn’t the power to harm

man himself in any way but through moral influence. It is the loving

and forgiving father who decides to renounce his chess pieces

according to their fealty to his tenets—the rules for deserving his

love. He might also sacrifice a pawn to a side-bet with Satan as he did

in the sad case of Job, and sometimes, in his ire at losing the

contest, he might simply wipe the board of all its pieces until his

temper calms.

Lucifer yearns for the heavens and God’s, his

father’s, love, but is relegated to darkness and

immoral suggestion not because he is himself immoral but as an

expression of his resentment toward a father who doesn’t

recognize his son’s value, who doesn’t hold him in

a regard equivalent in degree to his own self-esteem. He tries to prove

his worth by showing he has an equal power over men. Lucifer says to

God that he will distract man from “…Thy right

path” because “…Thou hast sent me

astray”, he doesn’t disagree with God, he is merely

at war with Him because they both want the same thing: the power of

decision.

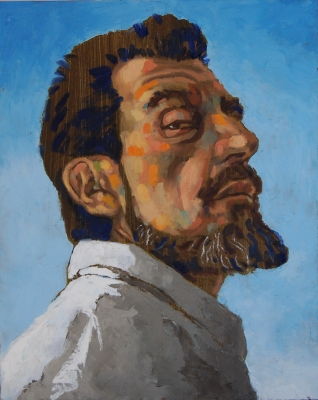

He must have been the most dashing, charming

and impetuous of all God’s sons whether they be

Christian angels or Muslim jinni.

He must have been the most dashing, charming

and impetuous of all God’s sons whether they be

Christian angels or Muslim jinni.

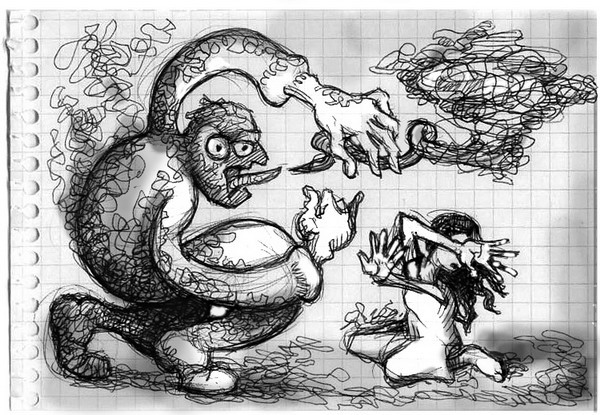

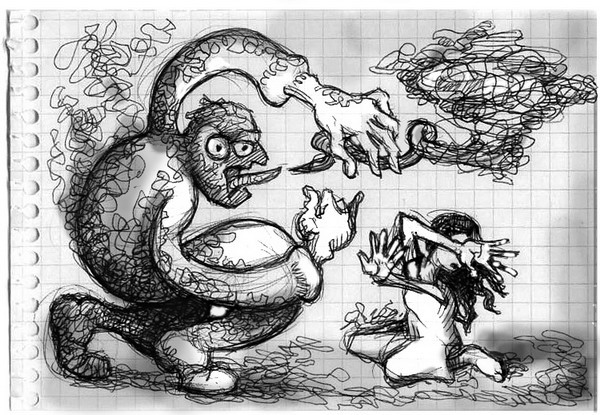

Lucifer wreaks evil, contention, conflict, cruelty, jealousy and

covetousness, using as entry his own sin as reflected in man: a

weakened will due to conceit. He cannot just walk up to men and

ask: “Would you like fifty years of unobstructed earthly

pleasures in exchange of an eternity of cruel torture in the fires of

Hell?” but he can whisper to

man’s vanity that he deserves more beautiful women or more

power over other men and if his innuendo is so tantalising that

the man succumbs to their allure to the point he suspends his ability

to calculate risk; and as consequence he persuades himself of the

rightness of a wrong and commits a moral crime, he tacitly

relinquishes his faith in God in order to do so—thus earning His

chastisement. It is neither man’s soul nor a pleasure in its

punishment that attracts the devil but rather his need to prove himself

to his father.

If Freud was right about anything he couldn’t have been more

right than in his concept of the Oedipal complex: we all know God, we

know he will never accept his son’s view of things, will

never let him sit to his right, will always expect him to bow before

him.

Among men the need to better one’s father, the challenge of

graduating to his strength, is either reached or not- it seems to me

that unless Lucifer repents with sincere contrition and asks His

pardon, God and he are locked in a battle that must end in

victory for one only, and perhaps even in the death of the other.

Tempting men with sweets that make them forget their teeth will fall

out if they eat them, must be easy enough, but still, there must also

be many who hold out through the vale of tears for the big dessert at

the end…

If I were Lucifer, filled by a sense of

righteous antagonism toward the injustice my father showed me, I would

probably learn to disguise the real import of my tempting suggestions

to try to fool those rational, or perhaps just dispassionate enough, to

resist being lured by the short money. I would imitate my enemy in

appearance; I would not entice to evil but represent evil as good. It

is clearly easy to make a good man kill by telling him it is good to

kill bad men, after that it is only a question of defining 'bad men'.

In fact it takes little more effort than a children’s

textbook like Der Giftpilz, to turn fellow men

into creatures foreign and odious to the species that reads it:

‘The boy goes on. "One can also recognize a Jew by

his lips. His lips are usually puffy. The lower lip often protrudes.

The eyes are different too. The eyelids are mostly thicker and more

fleshy than ours. The Jewish look is wary and piercing. One can tell

from his eyes that he is a deceitful person."

"Jews are usually small to mid-sized. They have short legs. Their arms

are often very short too. Many Jews are bow-legged and flat-footed.

They often have a low, slanting forehead, a receding forehead. Many

criminals have such a receding forehead. The Jews are criminals too.

Their hair is usually dark and often curly like a Negro's. Their ears

are very large, and they look like the handles of a coffee

cup."’

"From a Jew's face

The wicked Devil speaks to us,

The Devil who, in every country,

Is known as an evil plague.

Would we from the Jew be free,

Again be cheerful and happy,

Then must youth fight with us

To get rid of the Jewish Devil."’

Few among us today would fault the man who kills to save his own life

in self-defence, nor the life of another for that matter. But up until

recently certain European countries as well as the United States,

routinely pardoned such murders as the crime passionnél,

it being understood that when a good, God-fearing, Christian

man’s honour had been so far trespassed as his wife taking a

lover it was only natural he kill him and/or her.

In the cannibal tribes of the south

Pacific eating people was not exercised as a form of nutrition but

rather as a ritual of their religion. The boy couldn't become a man

until he had ingested his enemy's spirit through his flesh. What, you

ask, of the one eaten? He is added to the family altar to be remembered

as an honourable and valiant warrior who died fighting. According

to Judeo-Christian beliefs this behaviour is unmitigatedly

reprehensible but one can see, without needing to agree, that in the

cannibal's paradigm it is anything but evil.

It only took a blink of an eye after the

second world war to change a nation’s grateful camaraderie

with their Russian allies to fear, loathing and a finger on the

big red button. Normal, law-abiding, ordinary, family men have been

caught up in their country’s racial, economic or political

genocides (i.e. mass murders) all over the world and throughout

history. We little chess pieces really have no way of judging who sits

on which side of the great board and are most likely to believe

the one winning the game is the good one.

What if Lucifer won long ago? What if it is he who rules the heavens

and God who is shackled in a dank basement? The ruse maintained,

for fear of our rebellion. If he used this tactic it could mean that

the ten commandments with its amendments and addenda (allowing,

for instance, the militant Holy Roman Empire, the robbing of weaker

cultures for the greater glory of God, or even the saving of souls

under the threat of death) are precisely what win us an age suffering

the tortures of the damned… maybe turning the other cheek is

in fact evil and ‘an eye for an eye’

(especially if you take yours first) is actually good, it is only one

man's word, or strength, against the next which decides.

* What is a theologian, after

all, if not a philosopher with restricted access down certain avenues?

A theologian must rationalise forgone conclusion, a priori

premises, while a philosopher is at liberty to follow reason unfettered

to truth. Return

disclaimer: none of the above reflects my own

opinions, I don't base my beliefs on theological questions, I just find

them and their conundrums or paradoxes, interesting to consider.

Saturday

August 15th, 2009

Timelines

(100 words)

I read something I think was interesting

in a commentary about a life-long correspondence between two authors

who hardly ever met in person.

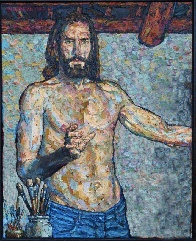

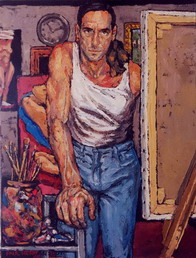

It talked of how an artist has two timelines, two histories, one led

and marked by his experience while the other, by his artistic

evolution. And it remarked how the histories may or may not

coincide; a high point of the creative evolution might cross a low

personal point and vice-a-versa or, indeed, any other combination

of possibilities.

Although it seems a little obvious now that I’ve read it, the

truth is I had never thought about it quite that way.

Monday

August 10th, 2009

Life's funnel

(540 words)

I was talking to my old friend Joe about

life and death. We talked of those who belong to our group: those

of the age for hindsight. I mentioned how many I knew who regretted

their choices, even some who I knew when they embarked,

enthusiastically, on the road that has disappointed. Of others who seem

lost, who gave their lives to their families and at fifty wonder

who they are aside from fathers, husbands or workers. And even those

who are disenchanted without realising they are disappointed, those who

live unexamined lives.

When I asked him how he felt about the shortening funnel of life he

thought I meant it as a metaphor for time (which is more like a

snowball rolling down a snowy mountainside!) but the image of a funnel

comes to me in terms of experience.

Nearing fifty I think of the large amount and wide range of

sometimes indiscriminate experience that lies behind, and how in

forming me it also made a better judge of me; hence the funnelling

which, with a narrowing of options also provides greater

distillation—the decreasing breadth of choice, becomes augmented

focus. And with age

comes a cumulative power drawn from understanding one’s self,

one’s abilities, one’s failings.

Joe, who is a successful scientist, summed up his feelings about his

life thus:

"Good luck kept me legal and alive. Good fortune led to my present

career. The sweet angels brought me my wife. My contribution

has been a sufficiently creative intellect to be valued as a

contributor among more staid thinkers. I never wanted to "work hard"

and I've succeeded. I've never "tolerated authority" and I

have none over me. I always cherished the feeling of getting away with

something - whether skipping school, church or work. That liberating

sensation of being free, unaccountable, and somehow special has endured

from a young age."

Joe and I have known each other most of our adult lives and

have often commented on how different our roads are just as we have

each observed in the other, where the road not taken leads. For myself,

despite the big errors, the bad decisions, the harm I’ve

caused, the events and consequences that show themselves poor in

retrospect, the ones I might pluck from my past given the power to do

so, I am satisfied by who I am and confident all tomorrows will

be stupendous just as I cherish the memories of my

past good and bad together. I know it takes mistakes to

‘become’.

A man cannot be truly honest until he has

stolen and regretted it. And I realize I wouldn’t

really change a thing about my past, about the person who committed

those mistakes, nor would I exchange my future for another’s.

The better judge I have become, the one who might change certain

moments of the past if he could, wouldn't exist if he did.

I've been reading thoughts about death by minds remembered for

thinking about such things and after life Joe and I talked

of death, and I thought his comment was really rather good in

comparison: "I know I am mortal and my life will end, but not today,

and not tomorrow either..."

Friday

August 7th, 2009

Souvenirs

(630 words)

I love to walk. And so, where many like beaches, I like mountains. On a

beach everything is always the same, every sunset or sunrise (depending

which side you’re on) is routinely beautiful; while in the

mountains every hundred paces, up, down or across, is new, and

every sunset or sunrise (or both if you climb to the top) is a surprise.

I walked in my mountains today, as I do every day, with my dog: Egon,

just as we did at five o’clock this morning under the full

moon when every shadow is an uncompromised ink spill and the

silent owls appear suddenly, great flying darknesses swooping too close

to one’s head.

They are not the most beautiful mountains I have known or lived amid,

but they are admirable in their own distinctive way the way mountains

always are, whether they be the breathtaking Rockies or Alps or

Himalayas or the rich, romance-laden Khyber range; salt and sand

shorn of all living things but goats, hawks and bandits. The

mountains I live among now are as much African as European, being as

they are, closer across the water to Morocco’s Riff mountains

than to Sevilla, the nearest city. If the mediterenean didn't have to

empty through this funnel, the channel would be no more than a pass

between mountains.

I often find souvenirs on my walks, a small animal skull, washed

and bleached; a fossilized seashell, 300 meters altitude, sixty

kilometers distance and fifty-five million years out of its

depth. Sometimes I find an idea for a painting or something I want to

write—I think best when I walk—and sometimes, I find no more

than a new memory I might recall sometime in the future.

Once it was a chameleon, that most charming of lizards, as big as my

extended hand without his tail. He thought he could fool me by moving forward and

back at every step, imitating the random movement of grass blown by the

wind instead of the linear movement of escaping prey; unfortunately he

was on clear, sandy ground and despite his subtle subterfuge

and sand-coloured camouflage, I could see his shadow as sharp as

cut paper.

As I moved toward him he gave up the drunken stagger and broke

into a full run whose speed turned out somewhat underwhelming compared

to my own. I snatched him up and looked at him and he at

me, his ice-cream-cone eyes moving in all directions at once as he

tried to take in the creature that now not only held him high above the

ground but also surrounded him. He opened his mouth wide showing me

past his small, sharp, serrated jawbone and deep into his body as

he tried desperately to bite me and I wondered: if I were

abruptly scooped up by the trunk of an elephant, would I have the

courage to punch him?

But we made it to the other side of the barren earth despite his threats,

where I let him go among the bushes lest he be picked up as falcon-food

before he could make it across alone with his ridiculous  swaying walk.

swaying walk.

Today it was six black vultures who caught my eye, sitting heavily in the upper branches

of an old, dead Walnut, one more circling above: an animal was dying

nearby. Beneath them an Egret followed a brave bull who grazed

unconcernedly but would, one day, die on the sword of a brave Matador.

The Egret showed no impatience for the food he finds in the earth

overturned by the bull, but walked beside him more than following him,

quietly

considering his last remark—his hands behind his back as if

courtesy

demanded no less than joining the bull in his lazy perambulations.

Thursday August 6th, 2009

Moon

Myths (580 words) Moon

Myths (580 words)

"Man is a credulous

animal, and must believe something; in the absence of good

grounds for belief, he will be satisfied with bad ones"

Bertrand Russell

We humans want so badly to know, to understand, to have definitive

truths, that we are ready to ignore absence of reasonable criteria or

lack of method, to jump to conclusions based on intuition,

sub-conscious impulses, hearsay and unexamined argument rather

than having to say: "I don't know." or: "It is merely coincidence."

It is thus, I think, that one hears so much superstitious belief

attributed to our moon’s influence by otherwise

discriminatingly intelligent people, like: More strange behaviour

manifests during a full moon than a waxing or waning one. If the moon

controls tides why shouldn't it be true that it has an effect on us

too? We, like our planet, are made mostly of water, after all.

One of the reasons people

think there is more unusual behaviour during a full moon is because

they don't distinguish clearly between a full moon and as many as

three days to its either side, making the chances of their believing

something occurred during a full moon, not one in thirty but one in

five.

When one sees strange behaviour

and thinks to look to the moon but finds it is not full, he

forgets the illogical connection while every time it is, he remembers

it, making it common that each one of us might remember something

bizarre we witnessed during full moon.

During a full moon there is more

light. Up until the recent invention of well-lit urban centres

the nights around full moon were the most attractive to venture out in.

Nights that are more populated also offer proportionately more

possibilities of aberrant behaviour being witnessed by others.

The moon's mass is one eightieth

that of the earth's and it spins around us at a mean distance of

38,000 kilometres in a circular (not eliptical) orbit. The tides are

caused by the moon pulling the oceans

from one side of the planet to the other through the effect its gravity

has on the world's own as the moon circles in its orbit. But the effect

the moon's gravity has on the world belongs to the physical

relationship between earth and moon, while the amount of light

the moon reflects, or conversely: the amount of shadow the earth throws

on the moon, is a function of the angle between the moon and sun

relative to the position of the earth—which has no import whatever on

its gravitational pull; i.e. just because we can't see the side of the

moon in shadow doesn't mean

it is not there.

Besides, the fact we are mostly

made up of water means that among the great variety of cells that make

up our bodies, on average, each is a little sac containing 60% water

with elements like the cell's nucleus, organelles and

mitochondria that swim about in the fluid carrying chemical information

to and from the cell's limits and it's nucleus. They can

only

move around or remain suspended because in a sub-cellular landscape

gravity holds no sway. If it weren't so, all the mobile parts of a cell

would simply lie at the bottoms of their little sacs of water making

life impossible (literally).

In other words: as we stand on

the earth's crust with ten kilometres of atmosphere held above us, the

planet's entire cumulative gravitational force cannot reach inside one

of our cells, nor could it bring an ant to crash under its own body

weight if it tried to commit suicide by jumping from the tallest

skyscraper, do you suppose the moon's could?

|

Wednesday

July 29th, 2009

神道 Shin tao

(The Way of the Gods) has roots

that go back to 500BC though it wasn’t formalised as Shinto,

both a path to wisdom and quasi-religion, until the 6th century

AD as an amalgam of incorporated harvest and clan traditions.

A typical Japanese might register or celebrate a birth at a Shinto

shrine, while making funeral arrangements according to the Buddhist

tradition. Unlike many religions, Shinto and Buddhism do not require

professing faith to practice, being centered more in ritual and

respect for the living spirit of each thing.

How chaos was subdued in the Japanese genesis myth

(680 words)

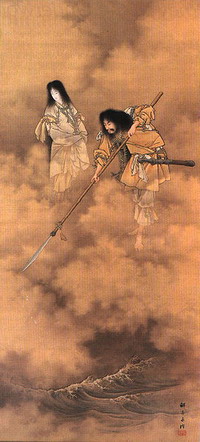

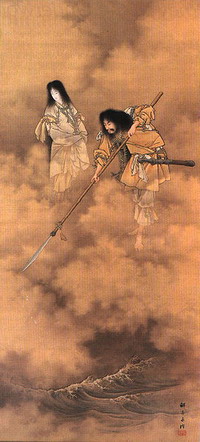

In the eighth generation the primitive

gods brought forth Izanagi, the inviting male and Izanami, the

inviting female (Izanagi-no-mikoto and Izanami-no-mikoto).

They lived in a great nothingness without height nor breadth nor depth;

without light or darkness, without colour or its lack.

Together they thrust their jewel-encrusted lance into the chaos which

was like a fertilized egg; as they stirred, its viscousness thickened,

and when they pulled the spear out, the last drops that fell from

its tip formed the islands of Japan onto which Izanagi, the inviting

male and Izanami, the inviting female, descended to erect the august

celestial pillar.

And Izanagi asked Izanami: How was thy body made? “It grew

everywhere except in one spot, and thine?” to which

Izanagi, the inviting male, answered: Mine, like thine, grew

everywhere, but more especially at one spot. “Were it not

good to place that part of my body which is in excess into that part of

your body in deficit?”

They decided to go ‘round the celestial pillar in opposite

directions. The female went left while the male went right and

when they met, she said: “What a beautiful and charming

young man!” to which he answered: “What a lovely

and loveable young woman!”

The woman showed willingness but it was the movement of a Wagtail that

impelled him forward. Izanami thus bore many divinities; light, rocks

and mountains, the breeze and stillness, the oceans

and their waves, plants, animals and subterranean grottoes.

Each, the rock or breeze as much as any animal or plant, with its Kami:

its spirit and its self-ness.

When Izanami gave birth to fire, however, she did not survive it.

Izanagi, the inviting male of  exalted and fruitful love, in a torment

of despair and stricken by grief, lay prostrate at the foot of

her bed and wept for his beautiful young sister.

exalted and fruitful love, in a torment

of despair and stricken by grief, lay prostrate at the foot of

her bed and wept for his beautiful young sister.

Thus he came to know his sorrow and his ire and he vowed to

rescue his wife from the underworld and bring her back to him,

but not before he killed he who had killed his love. But the fire God

not only would not be defeated but raged at every blow throwing off new

divinities right and left.

Izanagi gave up his struggle and went to find Izanami while

behind him one of the gods created during the battle, the impetuous

male, wreaked confusion and returned the celestial

world to chaos. In his impetuosity he broke the dykes of the rice

fields, attacked the palace and threw the stinking carcass of a

dead horse onto its rooftop. He left Amaterasu’s spinning

and weaving girls hurting in their most intimate parts and

even chased the Goddess who makes the sky resplendent, that is, the

sun, into seclusion thus turning the world dark and leaving it in

a desolation filled by terror.

Izanagi finds Izanami in the underworld as a rotting corpse and

she chases him away ashamed to have lost her beauty.

The gods come together to think up a

stratagem to control the impetuous male and his anarchistic

influence, finally tricking him into a cave and closing its

opening once he was inside. He could not escape back into the celestial

world but could drop down onto the earthly paradise of the eight

Japanese islands where he was both brutal and heroic. He killed a

terrible dragon that ate virgins and he bore a son who fought the

jealous gods and is remembered as a lover of undaunted passion.

Friday

July 24th, 2009

Noah Lukeman and the murky world of today’s book

publishing (760 words)

Noah Lukeman is president and founder of Lukeman Literary agency

in New York city; an agency that get books into print and on

bookstore shelves by offering them successfully to publishers who, in

turn, no longer deal with contract-less authors directly.

Making his agent’s fees, which easily account for greater

earnings than any single writer on his list, however, was not enough

for Mr Lukeman. Five or six years ago he broke into authorship himself

with a book titled How to Write a Great Query letter

with which he began making money from desperate writers who he would

not represent and whose writing he would not read, apart from,

and in addition to, the ones he does.

The downloadable pdf document with few words on few pages reached

best-seller status, so desperately optimistic are authors in this

shrinking printed book market. But despite recognising the exquisite

irony of a literary agent with no literary pretensions in his

literature, becoming a successful author by selling an instruction book

to would-be writers which teaches them how to talk to him, I bought it.

Although the pages my 25 bucks got me permission to print held no

secrets I could not find for free from multiple sources on the Internet

(like his less money-hungry competition or long lists of successfully

published writers who offer advice because they all remember their own

decade of rejections) it was at least concise and all in one

place- I did not regret buying it and it probably did indeed

improve my query letters.

I just received an e-mail from the Lukeman agency advising us writers

that in an impulse to give back to the writing community he has decided

to now (since May 2007) offer the same book for free but has in the

meantime, written another bestseller for the same market slice: writers

who want to find agents; and he also offers the wisdom of his

advice (i.e. telling writers which are the rules dictated by him

and his peers) on his Web-site whose link I clicked on.

It turns out it is no more than an offer to allow you to read his

comments in his own Site’s forum for a fee of twenty dollars

a month. Not a big investment which might even offer a pay-off for some

writers and yet, the leeching quality of his breaking into an

income stream generated from the very people he is meant to represent

is disheartening on principle, just as paintings galleries that rent

wall-space per square metre are: both are meant to glean their earnings

as middle-men from a sale transaction they themselves arrange for a

buying public, not directly from the creators of the product in

exchange of slim help in reaching a middle-man he, the middle-man,

offers.

His agency has a slush pile of so many manuscripts that they are not

accepting query letters and I wonder where, in a world that has

abandoned the arts—that teaches the young that books are no more than

repositories of information instead of worlds of literature (faster to

find from Internet sources than the dismal task of actually having to

read books), where will the next generation find the motivations to

become artists of any kind? And where will the world end up when it

finishes forgetting how important the arts are to every culture?

One might conjecture that in a world with exploding population

there would be a proportionate increase in that always small percentage

whose taste is more exigent, who want superior quality, who want

luxuries like art with their information. In-fact the growing number of

spending public means it is a bad business decision to pander to the

discriminating when the larger percentage of the market, the clueless,

is also growing exponentially- as always, with volume comes loss of

excellence.

addendum:

Today I read an article about a certain Baroque painter from the

lowlands whose work the New York Times, whose proofreading is routinely

flawless, described as Caravagist; and I found myself wondering what

was wrong with the term traditional to sometime after Caravaggio's

death of Caravaggiesque? Must a Rubenesque nude also now become

Rubinist?

This same modern efficacy where shortening a word presumably

to save either the writer the physical task of having to hit four or

five extra keys, or the reader the mental task of having to orient his

mind around so very many symbols, that works as metaphor for the loss

of poetry in modern prose.

Monday

July 20th, 2009

Morality and religion (490

words)

I suppose there are still people who believe religion fortifies moral

infrastructure; here in Spain it wasn’t long ago that

children were allowed to opt-out of Catholic training though they still

pray in public schools daily.

At first they changed the class from religion, i.e. Catholicism; to the

comparative study of religions, although the only relativism taught was

how correct Christ’s teachings were when compared to all the

other, silly, religions. When Franco’s pall was finally

lifted after nearly 30 years of slow change and children really

had a choice about being indoctrinated with their ancestor’s

religious beliefs, they were then offered the choice between religious

study and ethics, as if without

the former they had no way to learn the latter.

As if without a fear of God, a fear for one’s own immortal

soul or the threat of some kind of retributive punishment after death,

we would just throw our hands up and say: “Well, since

it doesn’t matter anyway I might as well drink blood squeezed

from live babies!” In fact, in my experience, there are as

many good people and villains among the

demographics of theists as that of atheists.

Indeed, if we looked more closely at some widely agreed moral

infraction like say: paedophilia, I bet we would find that men forced

to celibacy for their religious practice are the more frequent

offenders.

So why don’t we, the unafraid of divine wrath, go on

rampaging binges of wildly sinful behaviour? In part, I think, it is no

more than the fact our basic biological motives: the altruism that

serves both society and the altruist, empathy that impels us to

feel the pain we inflict on others, or the sympathy to turn the tables

on ourselves when considering the personal advantage taking from

another would attain—seeing ourselves reflected in our potential

victim’s eye, is largely due to an innate socialising

instinct that stems not only from our need to live in collaborative

fashion with others of our species but even more, just like dogs, we

become confused in our own identities when out of contact with our

taxonomical peers.

There is also self-image which is attached implacably to the

self-esteem which suffers when our judgement, skewed by self-interest,

allows us to cross our own moral boundaries. To a Christian this poses

a lighter threat to his psychic well-being since once the pleasure is

lived and real contrition arrives, his loving God will forgive

him—it is a far more difficult thing to acquire one’s own

forgiveness and nothing, after all, is harder to live with than

remorse.

So apart from it simply not being true,

if religious beliefs are also neither consolation nor moral pillar, I

think the main reason left for clinging to an imaginary friend is the

value and verification of a caring witness to our existence, just

as a parent is for a child.

Saturday

July 18th, 2009

Music and Love

(280 words)

Some friends and I went to see Omar Faruk

play in the old Moorish gardens of Jerez under a crescent moon last

night. We, the audience, had the added luck to have Arto

Tunçboyaciyan join Faruk and his five-man band, adding

his talents and humour to the proceedings.

At one point Arto, the Turk, looked across the stage at I’m

not sure which, either the Greek keyboardist or the Israeli Jew on

guitar—perhaps both, and said: if we can

make music together all men should be able to get along; and

Faruk added: “What Sufism has taught me is that we

needn’t all love one another as long as we just respect each

other.”

And it made me think. Even I who was not grown in religious soil of any

kind and, I think, also most occidentals, know the Old

testament’s teaching about loving one another (Leviticus

19:18): “Thou shalt not avenge,

nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people, but thou shalt

love thy neighbour as thyself” is impossible to accomplish

among mere humans and yet I had never questioned that, as an

ideal, if we all loved each other as we do ourselves the world would be

much improved.

When I thought about it more deliberately however, I realized that not

only is our own capacity for real love limited to a small number of

subjects but that it would be anything but nice

to be loved by everyone else.

If we reached for less than love and just respected

each other as we do ourselves instead, it would not only be enough but

preferable.

Click

here

to hear something by Faruk

Friday

July 12th, 2009

Temeris Mortis (1090

words)

'Men, commonplace and

ordinary, do not seem to me fit for the tremendous fact of eternal life.

With their little passions, their little vices and virtues, they

are well enough suited in the workaday world; but immortality is much

too vast for beings cast on so small a scale'

SOMERSET MAUGHAM

As this collection of thoughts and

stories, which I call my Mental Workshop, grows

older—four years old a month ago—I see trends reveal themselves

that reflect my mood, or the reflections consequent to my reading

and conversations of the time. Periods of months together about

art, theology, science, or the eternal mysteries of relations between

the opposing genders of our species, (i.e. love). It is sometimes

light-hearted sometimes gloomy, sometimes proud, at others insecure:

and the collection of written reflections becomes in itself a

reflection for their author.

I have been reading Julian Barnes’ Nothing to be

Frightened of, yet another book by an old man writing about

death: “…fear of death irrational?”

Barnes asks, and answers himself: “Why, it is the most

rational thing in the world—how can reason not reasonably detest the

end of reason?”

Soothing reading I guess, as Montaigne believed: Since we cannot defeat

death, the best form of counter-attack is to have it constantly in mind

in order to make its abyss appear less formidable.

I am long familiar with Barnes’ shorter work which I have

always read with admiration for his dominion as word-smith but upon

reading my first book-length composition by him I realize he is so much

more, he is a master of the word and,

ultimately, that is where literature resides, in the word.

He describes being described by a literary critic with a coined word:

polyphiloprogenitor, because the critic said of him: “Barnes

is father to forty books and four children”.

An intriguing mind, don’t you agree?

The book gives him room to speak in what seems a breezy, spontaneous,

conversational tone while, in fact, he weaves a medley of ideas

and narrative in a complex web of self-reference.

Although I have yet to finish the book he has already provided me with

a rare insight into each’s own mortality, an original thought

added to the basket of old wisdoms and observations. He says all

of us non-old people imagine, naturally enough, our extinction as a

goodbye to life when in fact (for those lucky enough to reach

senescence) it is not a leave-taking from life but rather a goodbye to

old age.

It is heartening to realize that in a world newly turned away from the

wisdom of age, a world where the young know more relevant information

than the old who haven’t had time to assimilate or re-learn

an unusual century’s changes, there are still some things a

young man can’t know unless he is told by an old one.

Today I sat at a sidewalk café on a street of the ancient,

history-soaked, horse-trading town of Jerez de la Frontera while

waiting for a friend. As I idly people-watched I saw an encounter which

is common enough but with the difference that today I noticed it: two

young men who met accidentally in the street a few metres from my

table; close enough to watch but whose voices were drowned in city

noise. They fell into earnest conversation as if they really had

something to talk about instead of just exchanging polite noises:

dialogue instead of small talk. I was about to look away to see if my

eye fell on something more interesting when a woman walked past.

She was not a beautiful woman: middle-aged, thick-ankled and

generally unfit compared to the good-looking young men who talked to

each other. But she wore enough sexual symbols in her tight white dress

and pumps—in a place and climate where most women wear

flat, open sandals and light, loose clothing—that like a

baboon’s red and blue ass it drew the two

men’s sub-conscious through their eyes to watch her jiggling

gluteus maximus’, until they eventually disappeared from

view; the whole while maintaining their engagement in their

conversation with the conscious part of their minds.

And once again I had pause to consider how we primates are separated by

so very little from mere monkeys.

The conscious mind’s evolution has been so much faster than

the biology it stems from that it lies to each of us about a duality

which is a fiction in an attempt at social contract between the

fundamentally dissociative elements.

If my example of the men’s eyes

being drawn to a woman they would not be consciously interested in, is

an example of biology’s rule, and their conversation a

manifestation of the higher, conscious mind (the one we like to think

of with free will), then it follows that if I weren’t

convinced just as you are that we are each indeed two: me and my

mind, the witness and the subject, my mind and the brain it

watches dispassionately, I would be able to fuse the two into a simple

‘me’ thereby getting rid of the only one who finds

death abhorrent, the one who imagines himself its witness.

addendum:

When Mr Barnes indulges in a prophetic look at his own worst-case

demise he sees it as being: "...preceded by severe pain, fear, and

exasperation at the imprecise or euphemistic use of language [by those]

around me."

The last time I was in L.A. someone asked

me that quintessentially Californian question (from within my European

kinesphere): "But are you happy?" I thought a moment in an attempt to

answer such a complex but direct query with a direct answer but could

only think to say: "When I am alone I tend to simply serious..."

And so, in this New Age world where I seem

surrounded by those who dedicate themselves to achieving a state of

emotional complacency; devotedly escaping what they consider negative

emotions, if asked about the pseudo-debate between the relative values

of intellectualism and emotionionalism, I would have to answer as

I imagine Barnes might: In my beliefs I strive for rationalism while in

my behaviour I am slave to emotion. My puny mind (or should I say:

brain?) sees paradox where all around me see unity.

If it weren't for the doubt I harbour

about my own sanity pointing to the probability I am actually not

insane, then there really would be very little room for doubt at all;

but finding books like this one provide the grace that if I am, I am at

least in interesting company.

Friday

June 26th, 2009

The Dream

(110 words)

Last night I dreamt of a beautiful house I once lived in for a time. In

the dream I remembered its every detail, its every room and

shelf, and how it stood on a hillock hidden by carefully tended

gardens.

I asked myself who had loaned it to me,

because I remembered it hadn't been mine, but couldn’t

recall; I then ran a number of countries through my mind trying to

place its location but without success. Still without waking and

frustrated by the lacunas in my recollection, I realised the memory was

real but the house was not, what I remembered so vividly in my dream

was another dream.

Saturday

June 14th, 2009

Peace (1440

words)

I have a dear old friend who is Christian, his name is Bob. We usually

live in different countries though we met when we both lived in London

and later, we shared NYC. Since then our long friendship has been

kept alive by sporadic correspondence of great volubility spotted by

occasional meetings, one of which I enjoyed in the form of a recent

visit.

As always we discussed philosophy and theology while: I took him out

sightseeing, between mouthfuls of food and when we weren’t

occupied otherwise in general.

He once again brought up de Caussade, the

early-eighteenth century Jesuit priest, theologian and mystic who has

been a particular inspiration to Bob’s faith and moulder of

his attitudes toward life.

Bob’s description of de Caussade’s central thesis,

Abandonment to Divine Providence, goes something like this: Evil must

be part of a plan too complex for us to understand since a perfect God

could only create a perfect world. This reminded me immediately of

Candide and since Voltaire published Candide in 1759 I wondered if his

sarcasm wasn’t directed at de Caussade. When I looked it up I

found Voltaire was lambasting Leibnitz instead, the brilliant

Rationalist who nevertheless is remembered better by history in his

alter ego as Voltaire's Dr Pangloss. After each of the terrible

calamities that happen to Candide or which he witnesses, his tutor, Dr

Pangloss, reminds him: “All is for the best in the best of

all possible worlds"

Besides, it turns out de Caussade was so fearful of the Church

fathers’ possible charges of quietism that his writings

weren’t published until 110 years after his death and even

then in a version censored by a fellow Jesuit because of the

impossibility of escaping punishment under the totalitarian Catholic

regime otherwise. Meaning effectively, that he wasn’t

published unabridged until 1966, nearly a quarter of a millennium after

he wrote.

De Caussade’s less simplistic credo actually went more like

this: The present moment is a sacrament from God and self-abandonment

to it and its needs is a holy state. Which, in turn, sounded to me more

like a Buddhist derivate such as Bodhidharma’s Zen.

Although when I thought about it, I realised the similarity in

conclusion obfuscates the very different reasons for reaching similar

truths: De Caussade’s abandonment is, in fact, leagues from

Buddha’s detachment.

My thoughts then took me outside the set of theology and into

philosophy where I found memories of Epictetus, the Greek

slave-philosopher.

I have always had a soft spot for that great thinker trapped in a life

as muddy as Job’s. As a slave to a cruel master, anecdotes

abound, like the one where his master, Epaphroditus, amused himself by

twisting Epictetus’ leg. Because of his philosophy (it is

said) he was able to look on dispassionately, even warning his master

that if he continued thus he would soon break the leg and be

master of an incapacitated slave; and didn’t shout-out when

his master went on to break it.

Epictetus centred on his belief that suffering arises from trying to

control what is uncontrollable. The Buddhist-like detachment that

results from the discipline to accept the immutable, diverges from the

Buddha’s in that it strives ultimately for happiness.

When Epictetus advises: "Do not seek to bring things to pass in

accordance with your wishes, but wish for them as they are, and you

will find them" I think it is an

interesting philosophical considerations but self-defeating in

terms of getting what one can from the experience that is life.

I think a successful life, within

the context of ultimate purposelessness, is one that is noticed by the

one who lives it—one that has events important enough to the one

living them to make perduring and cherished memories; peace,

balance, equanimity, denial of passions all lead to the opposite:

negligence and lack of engagement.

Epictetus himself may well have found all

the reach of life’s possibilities within the small range

available to him—one that includes living the full 1 to 10 scale

where 5 is acceptance, 10 is joy and 1 is desperate

melancholy. But in-fact his life was a pathetic example of what it

might have been given the full gamut of possibilities you and I,

as our own masters, can hope for.

To me it is clearly a slave philosophy

formulated as a reaction to Epictetus’ circumstances when

compared to say: Socrates, who refused to live any way but that which

he considered correct even when faced with execution by the state.

Epictetus' acceptance, like Buddha’s detachment or de

Caussade’s abandonment, seem to me, more resignation than

peace.

Rather than being a

sophisticated attitude that aids the experience of life, the

resignation is one for which one must exchange the highs and lows

that make memories. Predictability is a poison that dries the sap of

experience and what could be more predictable than knowing

everything is okay simply because everything is always

okay?

Although Bob and I both realize our ongoing debate is futile in

the sense that we argue from different platforms which overlap but do

not coincide: theology and philosophy. But it is only futile if

our objective is to convince the other or change his point of view

because Bob’s lively mind inspires new considerations

and thoughts in mine regardless, and I hope the same is

true for him because it in itself, is a rare enough pleasure…

To my arguments that life is in an essential way, the accumulation of

its memories, Bob answered recently: “Memories may be

important to you, but to me they're not. At my age {65} I can't

remember a damn thing! Barbara {his 17 year old daughter}

sometimes says, 'do you remember when we did this?' But I

never have any memory of it.” I answered: “And thus

you prove my point: If you don't live for the production of memories

you will end in the sad condition of having none and wondering

what you did with your unique and

singular life.”

When I spent time in a Buddhist temple (as novice in

Thailand) I watched the monks in their daily life and

found them (to differing degrees) at peace if not spiritually, which is

difficult to decide through observation, at least in the quiet

acceptance of a perfectly predictable life—just as many feel in

prison—but as examples of 'life' I'd say that at their ends they will

have only made one memory of the entire experience instead of the

variety and depth of those who strive instead of accepting.

We toss words like ‘joy’ around easily, we

all know how it is defined in the dictionary and don’t

feel a need to describe our individual sense of it when talking with

someone else but in fact there is only a personal definition of joy; it

is equivalent to the highest experienced

happiness, not to a scale of the possible, i.e. if one has only ever

reached a 7 out of a possible 10 on the happiness scale it becomes

subjectively, the definition of joy. The 7 that thinks it is a 10 will

not have any way to know it has missed something until the day it

reaches 8.

When Bob, who has led an unorthodox life

largely dedicated to reading, writing and the search for truth,

talks of his self-doubt in his observations of the differences between

his life and those around him (he still lives in NYC) he uses the

metaphor of the piglet who built the house of bricks and says:

“…those who planned for their retirements—even

early retirements—seem to have some nice and recurrent highs, as

they have virtually no financial worries, travel all around the world,

and spend most of their time following their bliss in doing various

projects” I answered: “I think the pig who builds

the brick house (sacrificing present for future) isn't the sort who can

really: ‘...spend most of his time

following his bliss.’ Of history's great men in any

field- few lived as sensibly you describe- it is a bourgeois construct

and ideal.”

Again, in a context of a pointless,

existentialist universe: what difference does it make? But in terms

of personal experience: I think it is a waste of a lot of

potential, a disregard for the possible and the unknowable fruits

of the unknown future. I'd say the proof is in the fact that difficult

experiences can become as cherished as memories as joyful ones, as long

as one lives them with a congruent personality.

Personally I don't believe happiness, much

less joy or bliss, are within the reach of those who suffer

peace.

Sunday May 17th, 2009

Sunday May 17th, 2009

God's Tick

(30 words)

I think the existence of ticks is enough

reason to cast doubt on the existence of God. Unless, of course,

God’s real purpose were the ticks and we other animals

merely their food source.

Saturday

May 16th, 2009 (removed)

He must have been the most dashing, charming

and impetuous of all God’s sons whether they be

Christian angels or Muslim jinni.

He must have been the most dashing, charming

and impetuous of all God’s sons whether they be

Christian angels or Muslim jinni. swaying walk.

swaying walk.

exalted and fruitful love, in a torment

of despair and stricken by grief, lay prostrate at the foot of

her bed and wept for his beautiful young sister.

exalted and fruitful love, in a torment

of despair and stricken by grief, lay prostrate at the foot of

her bed and wept for his beautiful young sister.

Much more than Michelangelo himself was able

to do. The evolution is clear when one looks at the ceiling, the design

becomes more laboured toward the centre as the, undoubtedly scary

and apparently infinite, unpainted expanse before him diminished.

He evidently became more drawn to the work for its own sake instead of

the pay Pope Julius II offered.

Much more than Michelangelo himself was able

to do. The evolution is clear when one looks at the ceiling, the design

becomes more laboured toward the centre as the, undoubtedly scary

and apparently infinite, unpainted expanse before him diminished.

He evidently became more drawn to the work for its own sake instead of

the pay Pope Julius II offered.